From the Ghetto to the Pure Land: Jodo Priests Working for the Homeless in Tokyo

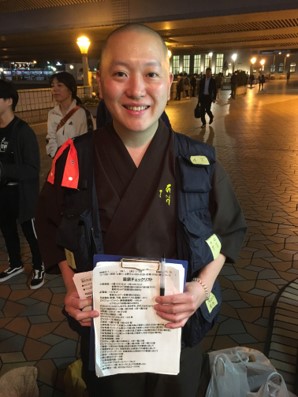

Our journey now takes us to Tokyo, retracing the footsteps of Rev. Nakajima to his alma mater, the Tokyo National University of the Arts, located at Ueno Park. Ueno Park is one of the great landmarks of the city, filled with popular attractions like Tokyo’s main Zoo and the Tokyo National Museum. At different points in the seasonal calendar, such as the Spring cherry blossom festival, it filled with revelers taking part in drink, open song, and dance. The park, however, is also known for its dark side, a place where refugees and orphans in the days just after the end of the war collected to sleep and beg for handouts. Today, it is also common to find a variety of homeless men from the aging population of migrant, day laborers who came to Tokyo from places like Akita in the heyday of the Japanese economic boom. Some are veterans of the park setting up night time activities for themselves outside of well-maintained cardboard “homes”. Others may be new and transient, getting a night of sleep on a stone bench with a plastic sheet for a blanket. On this one night in a gentle rain during Japan’s summer monsoon, we find a Buddhist priest, a few colleagues, and a small group of university students making their way through the park to locate every such homeless person they see and engage them with a friendly greeting, an oversized rice ball, and an offer of simple medicines and basic needs like clean underwear. One of the most striking moments of the evening is knocking on a cardboard enclosure and finding two women inside, happy to receive such gifts but also wary of strangers as women in a vast, dark park with uncertain dangers.

The Hitosaji “One Spoonful” Association was formed in 2009 by a small group of young Jodo Pure Land denomination priests to meet this ongoing problem of homeless that sprouted from the day laborer ghettos (yoseba) in Tokyo, especially the ones that spread northeast from Ueno Park, such as Sanya and Asakusa, and have become exacerbated during the economic crises mentioned above. In 2003, the Japanese government stated there were 25,296 homeless nationwide but mostly concentrated in yoseba such as Sanya in Tokyo, Kamagasaki in Osaka, and Sasajima in Nagoya. Most of them were single male day laborers, of which 2/3 were already in their 50s-60s. By September 2017, a Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare survey showed that 42.8 percent are now over the age of 65, the first time the number has ever gone above 40 percent, and the average age was 61.5 years old.[1] In 2018, the Ministry declared the number of homeless nationwide to have dropped to 4,977 nationwide but mostly in Tokyo 1,242 and Osaka 1,110, 95.2% of whom are men.

Given the declining state of the Japanese economy and the increase in irregular labor during this 15-year period, how could it be that the numbers could decline so much? The central government has responded in this period by supporting affected localities with more government shelters and halfway houses. Further, many of these men had not been deemed qualified for any welfare as able-bodied workers under the age of retirement but now into their 60s have begun to qualify for state pension and other forms of support. One lesser known fact is that the government conducts such surveys of the homeless during daylight hours based on those who “look homeless”. Considering many of the homeless have been long time day laborers, they are often out seeking what jobs they can get find during the day and only appear in various arcades and parks, like Ueno and the bustling tourist temple of Senso-ji, at night when there will be fewer complaints about their unsightly existence. The Tokyo-based nonprofit organization, Advocacy and Research Centre for Homelessness, conducts its own bi-annual survey with more than 800 volunteers going out at night, and they claim the real number is around 2.5 times the government’s data.[2]

Rev. Akinori Takase, one of the founders of Hitosaji and an Associate Professor in the Department of Social Co-Existence and the Buddhist Social Responsibility Promotion Section of Taisho University, explains a number of the deeper mechanisms behind the existence of the homeless. Firstly, he notes that about 60% of the homeless have mental disorders and 30% have “mild disabilities”, which can mean they have inadequate reading or writing skills. As such, it is often too difficult for them to fill out government welfare forms and to communicate their needs when the welfare system requires registration by applicants themselves. Others are far enough off the margins of society that they do not even know what they can qualify for.[3] Another factor that has caused such people from more actively looking for help are traumatic experiences from so-called “poverty businesses” (hinkon bijinesu). The most frequently cited type of these is called an “enclosure company” (kakoiya 囲い屋), which lures homeless people into apartment buildings they own or manage by acting as their financial guarantors—a stipulation required by law for such financial transactions. By acquiring a legal residence, these people can then apply for public welfare assistance, but these funds are diverted to the accounts of the enclosure company, which then syphons them off and leaves these people to survive on very little.[4] Yet another major threat to their existence are the cases of gangs of young boys and drunk men who enjoy assaulting the homeless. Rev. Takase explains that all these experiences make the homeless even more distrustful of others and convince them to try to live without any help.[5]

Reigniting a Tradition of Care and Social Welfare for the Marginalized in Buddhism

The mass migration of Japanese from their rural villages to the sprawling metropolises of the Eastern Seaboard (tokai 東海) also brought great structural and cultural shifts to Japanese Buddhism. While a new breed of urban, lay denominations thrived and grew at a rapid rate along with the economy in the 1960s, the traditional monastic-centric sects have continued to lose ground in society over this period. With the depopulation of the countryside, many of the wide network of temples built during the Edo period are being shuttered while a single priest often takes over the responsibility of numerous temples in a region. Temples in suburban and urban areas experienced a period of financial well-being during the bubble economy but paid a steep price for this as they became increasingly confined to the work of Funeral Buddhism (soshiki bukkyo 葬式仏教) and marginalized from the daily lives of their parishioners.[6] No longer looked towards for educational, medical, end-of-life, and psycho-spiritual needs, the traditional Buddhist temple has turned increasingly inward on itself. Unable to survive on the dwindling economics of performing funerals and memorial services for an urban citizenship that has lost its connection with its family temple (菩提寺bodaiji) located in the countryside, Buddhist priests generally have to take up other forms of employment to make ends meet. Married and secularized during the Meiji period, they have become disconnected from their traditional monastic roots and have also become members of the Disconnected Society where their worth is generally not recognized by the wider public.

The young priests who founded Hitosaji were keenly aware of all these issues when they began the association. They not only sought to help the homeless but to also revive themselves, their temples, and their denominations by reigniting traditions of care by Buddhist priests that go back to its founding days in ancient Japan. Prince Shotoku—whom most consider the father of the nation despite the mythic identification of the emperor as the first ancestor—continues to inspire through the variety of public initiatives he created, often with a Buddhist influence. In 593, he established one of the first Buddhist temples in Japan called Shitteno-ji 四天王寺 that still stands prominently in the heart of the Osako metropolis. At Shitenno-ji, he created the first form of Buddhist social welfare in Japan with the 4 Vihara System (shiko-in 四箇院) consisting of: 1) the host temple itself (kyoden-in 敬田院) which included rice fields and cultivated lands used for feeding the needy, 2) a dispensary of herbal medicine (seyaku-in 施薬院) cultivated on these lands, 3) a hospital for the sick (ryobyo-in 療病院), and 4) a shelter (hiden-in 悲田院) for the needy and downtrodden.

Another inspiration for the founders of Hitosaji were the two great Shingon monks of the Kamakura Era, Eizon 叡尊 (1201–1290) and his student Ninsho 忍性 (1217–1303). These monks were well known for re-instilling the practice of the Buddhist precepts, which they felt had suffered a serious blow from the new Pure Land movement and its “single-minded practice of chanting Amitabha Buddha’s name” (専修念仏senju-nenbutsu)begun, ironically, by the founder of the Jodo sect 浄土宗, Honen 法然. In their interaction with and conferring the precepts on various social outcastes known as hinin 非人, especially lepers, we are reminded of the historical Buddha’s own work to break Hindu caste taboos through ordaining untouchables as equal members of the monastic Sangha. Eizon and Ninsho’s work went beyond just “religious conversion” to the establishment of numerous shelters to house lepers throughout the 1,500 temple network of their new sub-denomination known as the Shingon-Ritsu sect 真言律宗.[7] While these two monks were diametrically opposite to Honen and his disciple Shinran, they shared the same concern for the common person, especially the marginalized.[8] These two historical antecedents of Shotoku and Eizon, who lived during the two formative eras of Buddhism in Japan, helped to lay the foundations for the village priest’s involvement in a variety of social welfare activities in the community during the long institutionalization of Buddhism in the Edo period.

The early industrial period of the Meiji, however, brought both new threats and opportunities to Buddhist priests and these traditional social welfare roles. The great threats were the revisionist Shinto ideology of the Meiji regime from within the nation and the sudden entry of Christian missionary activity from outside the nation. The Meiji regime’s calculated policy of secularizing Buddhist priests as “common citizens” (kokumin 国民) began a process of social marginalization that has proceeded unabated since that time. There were a variety of Christian social welfare movements that entered Japan at this time that also portrayed Buddhism as backward and overly ritualistic.[9] The opportunity, however, was that Buddhist priests finally became untethered from the stultifying control of the Edo military state. Buddhist priests began to travel the world and have encounters both with Buddhists in orthodox Theravada nations as well as with westerners of religious and secular orientations that greatly enriched their perspectives.

By 1916, Buddhists had caught up to the social welfare activities of Christian groups in Japan and outnumbered their organizations 140-90. By the early Showa, around 1930, Buddhist social welfare groups had mushroomed further to 4,848 as compared to 1,493 Christian ones. These included activities for the poor, disaster relief, education, prison chaplaincy, and orphanages, which became a special area of focus through the establishment of such organizations like the non-sectarian Buddhist Child-care Association 仏教保育協会 in 1928.[10] Rev. Takase notes, however, that the imperial government was always concerned about Buddhist groups acting too independently, and they began to incorporate these social welfare organizations into their own social policies of control.[11] For example, they began to co-opt Buddhist priests who had developed humanitarian campaigns to help destitute factory workers after the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-5. These priests were used as “factory evangelists” to instill loyalty to employers, promote the ethics of hierarchy, and prevent worker radicalization by the socialist and anarchist movements that had grown in Japan during this time. It was not until the early 1930s that a worker backlash created a campaign to disband them.[12]

Indeed, this period is fraught with Buddhist figures who became heavily compromised by imperial and fascistic culture. For the Hitosaji founders, two of their own Jodo priests were important alternative voices who spoke and worked for the marginalized of that era. The first was Kaikyoku Watanabe 渡辺海旭 (1872-1933), who grew up during the heart of the Meiji period and was ordained as young teenage boy at a Jodo temple in downtown Tokyo called Genkakuji—now not uncoincidentally one of the sites of a Jodo initiative to support the carers of the elderly and dying called the Carer’s Café. Under the tutelage of the famous Jodo patriarch of the early Meiji, Rev. Gyokai Fukuda, Watanabe developed an understanding of Buddhism for this new modern period that re-emphasized the monastic precepts—another ironic point due to Eizon’s own movement to revive the precepts as a reaction to the birth of the Pure Land movement. Watanabe was also a leader in the New Buddhism (shin-bukkyo 新仏教) movement, which developed a progressive interpretation of the teaching of the “four objects of repaying benefits” (四恩 shi-on) by emphasizing one’s debt to sentient beings 衆生恩 through social activism, rather than the reactionary interpretation of repaying one’s debt to the emperor through loyalty to the state.[13] Emphasizing these ideas showed his concern with modern forms of suffering and their economic and social causes in line with the 1st and 2nd Noble Truths, rather than the common, reductive tendency in Buddhism to view suffering as the cause and fate of individual karma.[14] As such, he also criticized the emerging forms of social welfare of this period that came from an elitist charity of offering aid to the poor with no sense of solidarity or interbeing (kyosei 共生) with them. James Shields in his important work on progressive and radical Buddhism in this period called Against Harmony writes, “Of all the New Buddhists, Watanabe was the first to truly cross the ‘threshold of modernity’, in the sense of not merely recognizing the importance of social reform, but demonstrating an awareness of social and historical contingency, and the resultant conclusion that human beings have the capacity to remake society, which is fundamental to the archetypal ‘modern’ perspective.”[15] This perspective is evidenced in Watanabe’s use of the term “social Buddhism” (shakai-teki bukkyo社会的仏教), which can be seen as an early formulation of the now popular concept of Socially Engaged Buddhism with which the present members of Hitosaji identify. In 1911, he created the Jodo Shu Labor and Mutual Aid Society 浄土宗労働共済会, which was linked to the global Settlement movement to support the downtrodden in urban areas.

One of his young Jodo priest students at Shukyo University, now Taisho University, would take Watanabe’s work to an even deeper level of personal engagement and realization. His name was Ryoshin Hasegawa 長谷川良信 (1890-1966) who along with Toyohiko Kagawa 賀川豊彦 (1888-1960), a Christian layman, and Shugaku Suzuki 鈴木 修学 (1902-1962), a Nichiren denomination priest is considered one of the founders of the modern social welfare movement in Japan. In July 1912, shortly after the founding of the Jodo Shu Labor and Mutual Aid Society, he and eighteen other classmates at Shukyo University organized a campaign envisioned by Watanabe to buy cheap imported rice from China to sell at reduced prices to laborers after the poor harvests of the previous autumn had shot up rice prices—an issue that lingered and led to the explosive rice riots of 1918. In 1918, through the support of Watanabe, he became active in the Japan Settlement movement, paying specific attention to those suffering from tuberculosis and to the rights of women to gain formal education, the latter in which he remained actively engaged until his death. During this time, he himself moved into the notorious 200 Tenements slum (ni-hyakken nagaya 二百軒長屋) in Nishi-Sugamo near the campus of Shukyo University. As this work expanded, Hasegawa began offering medical treatment for simple illnesses and family counseling for married couples, eventually opening up a consultation center for human affairs and legal matters. There came increasing requests to systematize and organize this work, which Hasegawa obliged to by setting up the Mahayana School in 1919 for the upliftment of the poor and women. Branches of this school were set up in other parts of Tokyo sometimes with attached settlement houses for poor laborers. Hasegawa’s legacy also continues on in the Taisho University social welfare education program which he helped found in 1926; the Shukutoku Sugamo Junior and Senior High School originally an all-girls school that developed out of the first Mahayana School; and Shukutoku University which Hasegawa founded in 1965 specializing in social welfare fields like nursing and children’s education and thus attracting a high number of female students. In the Hitosaji group, we also see his direct influence both in the concept and in the direct engagement of these priests to support the homeless.

A final historical influence for the priests of the Hitosaji is shown in the very choice of the name of the association. Hito-saji in Japanese means “one spoonful” and comes from a famous story in the lore of the Jodo Pure Land denomination. A well-known scholar and practitioner of the Sanron school of Madhyamika and the Shingon school of Tantra named Myohen 明遍 (1142-1224), who was also the son of a Fujiwara court official, had been critical of Honen’s new, radical Pure Land teachings. However, he came to reconsider them through a visionary dream of Honen feeding a group of lepers rice gruel at the western gate of the Shitenno-ji Temple that Prince Shotoku founded and where Honen had spent time in practice.

From this dream, he concluded:

Sick people in the first stages of their disease are able to eat all such fruits as orange, citron, pear, and persimmon, but later they cannot eat even the like of these, being able only to wet their throats with a little bit of thin rice gruel just to keep them alive. This encouragement of the single-minded practice of the nenbutsu is really the same thing. The world is now submerged under the flood of the five corruptions, and the beneficent influence of Buddhism is constantly on the wane. Society is degenerating, and we are now like people afflicted with a sore disease. We can no longer eat the orange and citron of the Sanron and Hosso, nor the pear and persimmon of the Shingon and Tendai. There is nothing to do but to take the thin rice gruel of the nenbutsu to escape the round of birth and death.[16]

This declaration of Myohen, which set him off on a path of devoted Pure Land practice from his 50s until his death at 82, is found in the imperially sanctioned pictorial biography of Honen from the early 1300s that has a full illustration of Myohen’s dream. The “one spoonful” is a metaphor for Honen’s radical democratization of Buddhism by providing a practice of equal import and application to all classes of people.

Rev. Takase further explains the importance of this story for the way Hitosaji engages in their work: “The attitude is that, ‘We cannot save you or give you salvation. We cannot provide an apartment and cannot give you assistance to make a living. But we can stay with you.’ Through giving the homeless just one rice ball and some tea, we make sure to have a conversation with them as much as possible. We don’t want to be a one-sided provider. Trying to build interactive, horizontal relationships is important. In this way, many priests actually learn from the homeless and reflect on their own religious lives.”[17] These words echo the stance that Kaikyoku Watanabe had towards working with the marginalized in the Meiji and Taisho eras. They also resonate with many of the case studies found in this volume of the real work of Buddhist chaplaincy (a.k.a. Socially Engaged Buddhism) in which Buddhist practitioners engage directly with the suffering of others and provide a compassionate presence in supporting them to uplift themselves, which in the end is the only true path to liberation.

Rebuilding Bonds amongst the Marginalized and the Disconnected Society

In just visiting or actually taking part in Hitosaji’s activities, one encounters a figure that recalls Ryoshin Hasegawa and his time spent living among the marginalized in the 200 Tenements. In the heart of Sanya, not far from the tourist magnet of Senso-ji Temple in Asakusa, lies a small and very humble Jodo temple named Kosho-in. Its young vice-abbot, Rev. Gakugen Yoshimizu, was born and raised there with his elder sister in a typical post-Meiji nuclear Buddhist family. As the headquarters of Hitsosaji, it serves as the launch point of the bi-weekly street patrols where supplies are gathered and volunteers come to prepare rice balls and engage in lively banter from mid-afternoon to evening. The genesis of Hitosaji’s work lies in Rev. Yoshimizu’s engagement with homeless issues in another center of the homeless, Shinjuku, located on the west side of Tokyo. Back in 2004, a Jodo priest friend of Rev. Yoshimizu was asked by the Shinjuku Connection Association (新宿連絡会 Shinjuku Renraku-kai) to perform a memorial service for deceased homeless people from their community during the important, summer ancestral festival of Obon, when it is believed that the spirits of people who have passed away come back to this world to visit family and friends. Through this and subsequent annual services, Rev. Yoshimizu came to learn about the anxiety the homeless face in death since they have been cut off from their family relationships and in some cases even barred from being buried in their family grave plots because of the stigma of being homeless.[18]

To understand the sentiments on both sides, it is important to understand that Japanese in general do not hold as fast to concerns over heaven and hell as those from the Occidental Abrahamic traditions do. Furthermore, even as Buddhists, they do not maintain strong notions of reincarnation and the possibilities of being reborn as, for example, a cockroach for a bad life lived as do people from South and Southeast Asia. As a fusion of Confucian and Buddhist traditions, Japanese ancestor worship focuses on the maintenance of human bonds (kechi-en 結縁). In a more specific Buddhist context, this term can be referred to as “karmic connection” (en 緣), deriving from the term engi (縁起 Skt. pratitya samutpada), which means the chain of interdependent causes and conditions that the Buddha taught is the source of all phenomena rather than a creator God or eternal Soul. As such, Japanese typically view “heaven” as a Buddhist pure land where they will be reunited with ancestors and loved ones that have passed before them. On the other hand, the fate of those who have no progeny or loved ones to maintain such en through regular memorial services by Buddhist priests and grave visitations is to become a “disconnected spirit”, literally “disconnected buddha” (無縁仏mu-en hotoke), who wanders the earth unable to find companionship. In many ways, the homeless have already become mu-en hotoke before death.They, along with the growing number of marginalized people profiled in this chapter, fear this fate more than any vision of burning in hell at the hands of Satan.

Rev. Yoshimizu recounts a rather harrowing story of the fate of the homeless at death from amongst his own community. Upon learning that one of the regular homeless in the area had died, he and some other members went to search for his body at the local public crematorium. However, they were unable to locate the body, but remained steadfast in their search until they finally discovered that as a homeless person with no obvious family relations, the body had been sent to a separate crematorium for pets and animals—showing that traditional attitudes towards outcastes, literally called “non-humans” (hi-nin 非人), persist unconsciously if not consciously in modern Japan. A homeless man that Hitosaji encountered in their work expressed the fear of such fate and the hope for some kind of en: “Now we are homeless, but after death, we must be homeless as well. If we knew we had a place to stay in the afterlife, we could be more serious, and think about how to live life. If I knew that after I died, friends would come to my grave and talk about me, I would be able to strive more intensely in life.”[19]

From these types of encounters as well as the concerns of the members of the Shinjuku Connection Association, Rev. Yoshimizu was asked in 2007 to build a grave plot at Kosho-in temple for the remains of the homeless. In contrast to some of the financially well-off temples that sit on extremely valuable pieces of property in wealthy areas of Tokyo, Kosho-in’s location in the heart of Sanya shows that the growing social disparity (shakai kakusa 社会格差) of Japan also effects the Buddhist world. Rev. Yoshimizu himself earns his living as a lecturer at Shukutoku and Taisho Universities, and out of his own personal savings he paid for the tombstone that is engraved with the Chinese character for “bond” (yui 結).

From these types of encounters as well as the concerns of the members of the Shinjuku Connection Association, Rev. Yoshimizu was asked in 2007 to build a grave plot at Kosho-in temple for the remains of the homeless. In contrast to some of the financially well-off temples that sit on extremely valuable pieces of property in wealthy areas of Tokyo, Kosho-in’s location in the heart of Sanya shows that the growing social disparity (shakai kakusa 社会格差) of Japan also effects the Buddhist world. Rev. Yoshimizu himself earns his living as a lecturer at Shukutoku and Taisho Universities, and out of his own personal savings he paid for the tombstone that is engraved with the Chinese character for “bond” (yui 結).

As noted earlier, Christian social welfare groups provided an important stimulus to the emergence of Buddhist ones in the Meiji and Taisho eras. Today, the majority of religious groups that support the homeless in Japan are Christian, but this has not posed a barrier to Hitosaji’s work. It has teamed up with such organizations as the non-profit Sanyu “Friends of Sanya” Association (山友会 Sanyu-kai), which offers free medical care, lifestyle consulting, and hot meals to the homeless. The Director of Sanyu is Father Jean Le Beau, a Catholic missionary from Canada who has been working in Sanya for over 20 years. In 2015, Rev. Yoshimizu and he partnered to build a second grave plot at Kosho-in that would serve the Sanyu Association’s community. Rev. Yoshimizu collected the small traditional memorial tablets that Sanyu had made for their deceased members and interred them at Kosho-in, while also recording their death dates and keeping pictures of them inside the temple. Even Father Le Beau has requested that he be buried in this plot, which involves the unorthodox practice among Christians of cremation but is necessary as Japanese graves are not constructed to allow for the burial of large, individual caskets. Rev. Yoshimizu explains, “Although there are people who are important to us who are not blood relations, we divide and establish our burial plots according to blood relation. The Sanyu Association has brought together those who basically have no close relations and provides a place for building relations from which one can speak from the heart. It is important to build connections even beyond our blood relations.”[20]

In order to communicate this message of inclusivity and “connection”, donations for building the stupa were done through online crowd funding. To their surprise, they received a major response from the LGBT community. Echoing sentiments expressed by Rev. Hakamata back in Akita, Rev. Yoshimizu explains, “This is not just about the aging day laborers in Sanya. There are many people nowadays who are dying without anyone knowing. It seems that people are dying alone and that this dying without any connections or bonds is very lonely and sad. There’s really no limit to who this can happen to.”[21] Indeed, Rev. Yoshimizu tells stories of LGBT individuals who have not been allowed to be buried in their family grave plots at death due to the aforementioned stigma or impurity (kegare) placed on such communities and hence become “disconnected spirits” (mu-en hotoke). In this way, the plots at Kosho-in are providing a space for new intentional communities to “be together even in death.”[22]

As the numbers of homeless, people with no family connections, and abandoned grave plots have continued to increase in Japan, Kosho-in also constructed in 2015 a larger collective grave to hold such ashes—a place where Rev. Yoshimizu has also requested to be interred at death. This grave is in the form of a more traditional Buddhist stupa, the original invention of which was to house the ashes of the historical Buddha after his death in ancient India. The stupa has encased a statue called the Sanya Kannon 山谷観音, Kannon being the East Asian female form of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion. This Sanya Kannon wears a Christian cross around her neck, further symbolizing the ecumenical spirit of Kosho-in’s work. In September of 2018, Kosho-in also erected a tomb funded by a local nursing station. The medical workers there have seen too many of their elderly patients die alone. Having developed relationships of loving care, they have also wanted a place to venerate them and express their own grieving. By creating such connections, Kosho-in temple has become a place for these communities to visit for the regular maintenance of “bonds” and the creation of “inter-connection” (yu-en 有縁) through the Japanese tradition of praying in front of graves. This work continues to expand with yet another grave stone built in 2019 for Hope House (kibo-no-ie), a special hospice in the Sanya area built for day laborers who contract terminal illnesses from their dangerous work. Modeled along the lines of Mother Teresa’s Kalighat home for dying destitutes in Calcutta, it is has a Christian base yet Rev. Yoshimizu serves on their board of directors and provides chaplain care for the staff facing various challenges.

As the numbers of homeless, people with no family connections, and abandoned grave plots have continued to increase in Japan, Kosho-in also constructed in 2015 a larger collective grave to hold such ashes—a place where Rev. Yoshimizu has also requested to be interred at death. This grave is in the form of a more traditional Buddhist stupa, the original invention of which was to house the ashes of the historical Buddha after his death in ancient India. The stupa has encased a statue called the Sanya Kannon 山谷観音, Kannon being the East Asian female form of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion. This Sanya Kannon wears a Christian cross around her neck, further symbolizing the ecumenical spirit of Kosho-in’s work. In September of 2018, Kosho-in also erected a tomb funded by a local nursing station. The medical workers there have seen too many of their elderly patients die alone. Having developed relationships of loving care, they have also wanted a place to venerate them and express their own grieving. By creating such connections, Kosho-in temple has become a place for these communities to visit for the regular maintenance of “bonds” and the creation of “inter-connection” (yu-en 有縁) through the Japanese tradition of praying in front of graves. This work continues to expand with yet another grave stone built in 2019 for Hope House (kibo-no-ie), a special hospice in the Sanya area built for day laborers who contract terminal illnesses from their dangerous work. Modeled along the lines of Mother Teresa’s Kalighat home for dying destitutes in Calcutta, it is has a Christian base yet Rev. Yoshimizu serves on their board of directors and provides chaplain care for the staff facing various challenges.

Training Buddhist Chaplains through Engagement in “Birth, Aging, Sickness, and Death”

From their initial encounter of supporting the homeless in death through memorial services, Rev. Takase recounts that one priest in their group asked, “How much do we really know about their suffering?” He then explains that Buddhist priests often preach about how life is suffering and that it comes from excessive attachment and greed. However, he critically reflects, “We priests live in temples where we can have enough food and sleep on a mattress with a blanket. What do we know about suffering?” From this conversation amongst each other, the regular activities of the Hitosaji were born in 2009 with the creation of bi-weekly street patrols. Rev. Takase explains further, “Our view is that something special done by someone special can become nothing special done by everyone. In other words, people should do what everyone can do. This is more important than great works done by only people who have special skills and abilities.”

This “nothing special” begins around three o’clock in the afternoon every other Monday all year long in the tiny compound of Kosho-in. Here a number of early-bird volunteers and priests meet up with Rev. Yoshimizu to begin cooking rice to make some 300 extra-large rice balls and prepare a variety of simple material needs that will be offered, such as non-prescription medicines for cold, stomach ache, and pain relief and a variety of seasonal items such as gloves and socks in the winter or clean underwear in the summer. In recent years, a group of Vietnamese immigrants led by a Buddhist nun who studies at Taisho University has come early to prepare Vietnamese fried spring rolls to go along with the rice balls handed out. In this way, the compound as well as the main hall of Kosho-in becomes a bustling scene of volunteers preparing for the evening patrol and engaging in plenty of friendly banter. As anyone new to the event can feel, human bonds are being made just in this gathering of volunteers who may be Buddhist priests, people from the local community, students from Shukutoku, Taisho and other universities, and even a few homeless themselves.

This “nothing special” begins around three o’clock in the afternoon every other Monday all year long in the tiny compound of Kosho-in. Here a number of early-bird volunteers and priests meet up with Rev. Yoshimizu to begin cooking rice to make some 300 extra-large rice balls and prepare a variety of simple material needs that will be offered, such as non-prescription medicines for cold, stomach ache, and pain relief and a variety of seasonal items such as gloves and socks in the winter or clean underwear in the summer. In recent years, a group of Vietnamese immigrants led by a Buddhist nun who studies at Taisho University has come early to prepare Vietnamese fried spring rolls to go along with the rice balls handed out. In this way, the compound as well as the main hall of Kosho-in becomes a bustling scene of volunteers preparing for the evening patrol and engaging in plenty of friendly banter. As anyone new to the event can feel, human bonds are being made just in this gathering of volunteers who may be Buddhist priests, people from the local community, students from Shukutoku, Taisho and other universities, and even a few homeless themselves.

As the afternoon turns into evening and preparations are finished, the mass of volunteers that can number from 20 to 50 persons pack into the tiny Buddha hall of Kosho-in to engage in perhaps the only overt religious aspect of the work. For about 20 minutes, participants are led through a simple Jodo Pure Land Buddhist service with a common Mahayana dedication of merit for all beings and a remembrance of those who have passed especially in disasters like the Tohoku tsunami and nuclear accident. It concludes with extended nenbutsu chanting of Amitabha Buddha’s name with only the lights around the main image of Amida creating a deep feeling of connection with the divine.

Upon completion, volunteers with priests leading them are divided into 5 groups who will wander nearby areas that the homeless frequent: two are either sides of the Sumida River under the expressways where homeless take shelter; a third around Ueno Station and historic Ueno Park; a fourth around the shopping arcades within the great Senso-ji Temple at Asakusa; and a fifth that has been recently shut down through the old and decrepit Sanya shopping arcade on the edge of the Yoshiwara red light district. At this point, volunteers are all laden with some sort essential, from the heavier bags of rice balls to the plastic containers of Vietnamese spring rolls to bags of throat candy, medicines, underwear and so forth.

At a critical point before the patrols begin, Rev. Yoshimizu engages in a heartfelt explanation of the attitude and method of encounter with the people who will soon be met. From the sentiments of Honen, Kaikyoku Watanabe, and Ryoshin Hasegawa, Rev. Yoshimizu explains that it is essential to approach the homeless with kind awareness while bending one’s knees to attain the level of those sitting or sleeping on the ground. If they are inside a carboard box, perhaps sleeping, one knocks gently and in a soft voice introduces themselves as being from the Hitosaji Association, then makes a rice ball offering as one would make an offering to a monk in classical Buddhism. If the person is asleep, then one leaves behind a rice ball, a candy, and a small flyer identifying Hitosaji that provides information on nearby free medical clinics and welfare facilities. If the person is awake and responsive, the same offering is made and a simple conversation begins first by asking them about their health condition and offering any basic medicine they may need. The encounter may end there, but often is does not. Unlike the homeless in many other nations who suffer from more severe forms of mental illness and are often high on some sort of drug, Japanese homeless are often the elderly, day laborers documented in this chapter. They may actually be fairly productive during the day with some form of work. Some of them also show a spirit of strength and almost self-pride, for they were an integral part of building the Japanese economic miracle having worked in factories and construction sites all over the region and nation. A number of homeless are also regular “residents” of these areas and have developed strong bonds with Rev. Yoshimzu and the other priests of Hitosaji. In this way, an encounter may involve a hearty thanks for the regular food offering and a cheerful conversation even with some of the foreign volunteers that may join these patrols.

As such, one can see the importance of these patrols in “re-humanizing” these people by recognizing them as “normal folk” out in the busy streets of Tokyo where they are always made invisible by the neat and efficient urban resident. However, after numerous times engaging in this entire Hitosaji process, one comes to a deeper understanding of its impact. If, as mentioned previously, the priest and volunteer are supposed to overcome a dualistic sense of charity in which “us usual non-homeless people” give to and support “those poor homeless people”, then one should also understand that a transformation will occur in themselves as much as it will in the homeless receiving our kindness and aid. Indeed, in classical Buddhism, the Buddha established alms going for the monks and nuns as a form of “reciprocal giving” in which the monastic received their material needs while providing for the spiritual needs of the laity in dharma teachings. It is not surprising then in the upside-down world of Japanese Buddhism where priests are married and do not follow the monastic Vinaya, that Hitosaji would become a vehicle for priests to make offerings to and learn from the most marginalized of lay people, the homeless. This process is very much in line with the spirit of Honen and his student Shinran’s teaching of Pure Land Buddhism in which all religious hierarchies are destroyed, the priest-layperson distinction is obliterated, and the most downtrodden are the first objects of Amida’s great vow of compassion. In this way, Hitosaji’s activities have become a training ground for a new breed of Japanese Buddhist chaplain who are being cultivated by the Rinbutsuken Institute of Engaged Buddhism, for which Rev. Yoshimizu serves as a senior consultant and trainer. The Institute’s motto is to engage in the “birth, aging, sickness, and death”—the four inevitable forms of suffering—of the common people and to train Buddhist practitioners in compassionate listening and care.

The overall effect of Hitosaji’s work feels like the eradication of barriers and disconnections that lies at the source of the Disconnected Society. On a superficial level, common citizens see the homeless as “other”, at worst to be ignored or swept off the street and out of site, at best to be given welfare and economic aid to re-join “society”. This attitude posits the cause of homelessness in the individual and turns a blind eye to the deeper structural and cultural causes. We might view Hitosaji’s work as the basic charity of a religious group to help the plight of the individual homeless. However, the way it is structured and the way a culture of human connection pervades the entire process, one comes to an appreciation that it is working to rebuild the fabric of human relationship in the vast ocean of disconnection that pervades urban Japanese life. Indeed, the cause of homelessness lies less in the inability of some to maintain themselves in such a society as much as how all members of this society have become desensitized to human relationship and concern for others. By bringing a wide range of people together in the rather simple work of preparing rice balls for a few hundred people living in the street, the hundreds of people who may join Hitosaji over a one-year period find a new awareness, courage, and compassion to engage with others.

At the end of the evening, the five groups re-assemble in the shadow of Senso-ji and the giant new monument to Japanese consumerism and energy waste, the glittering Tokyo Sky Tree, for each individual to share their experiences of the evening. From the “sharing of work”[23] with priests and volunteers to the sharing of time with those living in the street, a much deeper sense of human relationship has been built and a feeling that it is not unusual to encounter someone new and unknown with a friendly voice and the making of eye contact.

GO TO Part V: Conclusion: Re-establishing Bonds with the Rural Homeland

[1] McKirdy, Andrew. “‘No one wants to be homeless’: A glimpse at life on the streets of Tokyo”. Japan Times. March 2, 2019.

[2] McKirdy. “‘No one wants to be homeless’: A glimpse at life on the streets of Tokyo”.

[3] Takase, Akinori. “Buddhism and Social Activism in Today’s Japan: The Activities of the Hitosaji Association”. Lecture given at Swarthmore College, March 19, 2013.

[4] Brasor, Philip. “Rising racket hoodwinks the have-nots”. Japan Times. October 10, 2010.

[5] Takase. “Buddhism and Social Activism in Today’s Japan”.

[6] Tomatsu, Yoshiharu. “Tear Down the Wall: Bridging the Pre-Mortem and Post-Mortem Worlds in Japanese Medical and Spiritual Care” in Buddhist Care for the Dying and Bereaved. Eds. Jonathan S. Watts & Yoshiharu Tomatsu (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2012), p. 38, 49.

[7] Matsuo, Kenji. “What is Kamakura New Buddhism? Official Monks and Reclusive Monks”. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 1997. 24/1-2, p. 186.

[8] Covell, Stephen G. Japanese Temple Buddhism: Worldliness in a Religion of Renunciation. (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2006), p. 97.

[9] Covell. Japanese Temple Buddhism. p. 99.

[10] Covell. Japanese Temple Buddhism. p. 99.

[11] Takase. “Buddhism and Social Activism in Today’s Japan”.

[12] Shields, James Mark. Against Harmony: Progressive and Radical Buddhism in Modern Japan. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 204. Davis, Winston. Japanese Religion and Society: Paradigms of Structure and Change. (Albany, NY. SUNY Press, 1992). p. 177.

[13] Shields. Against Harmony. p.103.

[14] Shields. Against Harmony. p.143.

[15] Shields. Against Harmony. p.118-19.

[16] Honen the Buddhist Saint: His Life and Teaching. (a translation of the 48 Fascicle Pictorial Biography of Honen Shonin Honen Shonin Gyojoezu–Shijuhachikan-den) Translated by Harper Havelock Coates and Ryugaku Ishizuka. (Kyoto: Chion-in Temple, 1925), Chapter XVI:2. p. 317. Now being re- edited and re-published by the Jodo Shu Research Institute in Tokyo.

[17] Takase. “Buddhism and Social Activism in Today’s Japan”.

[18] Takase. “Buddhism and Social Activism in Today’s Japan”.

[19] Takase. “Buddhism and Social Activism in Today’s Japan”.

[20] “Towards Reviving a Society with Connection (yu-en): The Hitosaji Association’s Work with the Homeless and Disconnected (mu-en)”. Bukkyo Times, February 9, 2017.

[21] “Towards Reviving a Society with Connection (yu-en)”.

[22] “Towards Reviving a Society with Connection (yu-en)”.

[23] “Sharing of work” or “sharing of labor” (shramadana) was a key conceptual and practice point in one of the most important socially engaged Buddhist movements in Asia, the Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement of Sri Lanka, in the latter half of the 20th century.