Gender in Japanese Buddhism

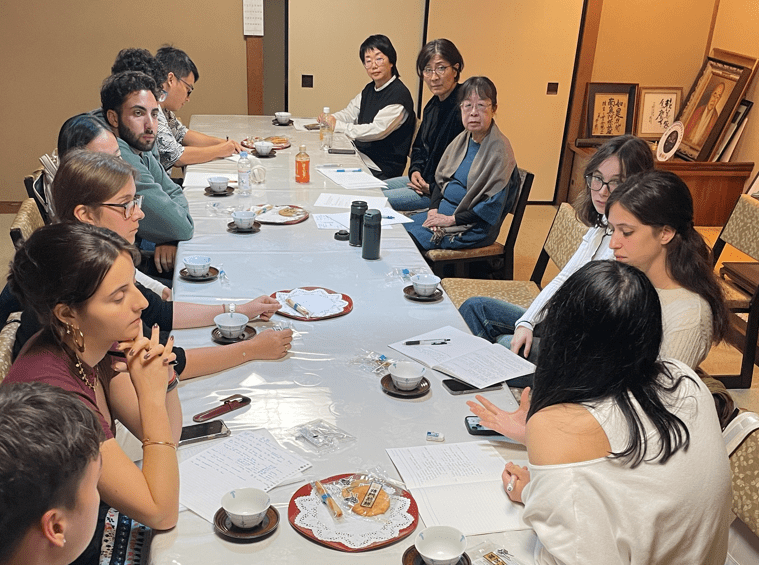

Ms. Misa Seno 瀬野美佐

former staff at Headquarters of the Soto Zen denomination

founding member of the Tokai-Kanto Network of Women and Buddhism

Shinko-in Temple, Tokyo

October 16, 2025

The first thing I want to say is that, in the Zen tradition to which I belong—specifically, the Sōtō school—there is, in principle, no inherently discriminatory teachings regarding gender. Our founder, Dōgen (1200-1253), even went so far as to criticize the practice of prohibiting women from entering sacred mountains (女人禁制 nyonin kinsei), which shows that he did not view women as inferior. Yet, in practice, Sōtō Zen has been, like other traditional Buddhist sects in Japan, a deeply patriarchal community that places women in a lower position. Why is that? Today, I would like to share two personal experiences to speak about this issue.

I was born in Mie Prefecture, as the daughter of a temple priest. As you may know, it is common in Japanese Buddhist traditions for male priests to marry and live at the temple with their families, and to pass the temple on to their children. The temple I grew up in was a small one—so small that it could not support our family through temple income alone. Still, when I was ten years old, I told my father, the head priest, “I want to become a monk.” But he refused and the words he used were: “If a woman inherits, the temple will lose its status.”

This was a deeply shocking moment for me. I might not have known the word “gender discrimination” at the time, but I felt crushed. Why should the temple lose its dignity simply because a women succeeded to it? Whenever I share this story with Buddhist clergy in Japan, they usually respond with something like, “Your father must have said that because he knew you would have a hard time if you became a nun. It was his way of protecting you.” Or, “That was an expression of his love.” Each time I hear such words, I feel disappointed all over again, because if I had been a boy, everyone would have been delighted at my desire to become a monk.

In fact, today over ninety percent of Sōtō priests are sons of priests. So why are daughters rejected? It is because female priests are seen as inferior. No matter how hard they work, women are judged to be inferior to men. And then people dare to call that love? But when I shared the same story with women who were either studying Buddhism academically abroad or engaged as lay practitioners, the reaction was completely different. They responded with words like, “That’s terrible!” or “That must have been so painful for you.” They grieved with me. They understood my feelings. That brought me great relief.

| Soto Zen denomination | 15,000 temple nationwide | ||

| Number of Priests Currently Holding Teaching Qualifications | Male: 14,636 (89 foreign nationals) | Female: 416 (52 foreign nationals) | Jizoku (wives of priests): 14,248 (10 male) |

| Aging of Priests: Percentage aged 75 or older | Male: 3,554 (25%) | Female: 219 (53%) | Jizoku (wives of priests): 5,103 (36 percent) |

Reflecting on why the responses differed so much, I realized something. In the Japanese Buddhist context, my own wishes never really mattered. What mattered was the father-as-abbot’s authority. If the priest, as head of the temple, declared something, it was unquestionably correct, and I was expected to obey. That obedience itself was framed as “love.” Underlying that logic is an assumption: women should obey men, because men are the ones meant to guide women. I believe this arrogance lies at the root of gender discrimination within Japanese Buddhism. As I later came to learn, my father’s words—“If a woman inherits, the temple will lose its status”—were entirely false. It took me many years to discover that truth, but that is a longer story I will not go into now.

Let me move on to the second episode. Being disappointed with temple life, I decided to move to Tokyo. I was told it would be acceptable if I attended a Sōtō-affiliated university called at Komazawa University. There, I began serious study of Sōtō teachings. When I was twenty, I was attending a lecture on the Shōbōgenzō, the great work of Dōgen. A fellow student—himself the son of a temple priest—challenged the professor: “What’s the point of reading this? Once I go back to the temple, my life will be nothing but funerals and memorial services, chanting scriptures I don’t even understand. This is useless!” The professor’s reply has stayed with me for over forty years: “You’re right,” he said. “It may be useless. But it will make your life beautiful.”

When I later shared this story, people often responded by saying, “So Buddhism makes life beautiful. That’s wonderful.” But for me, the professor’s words were meaningful only when kept together with his first phrase: “It may be useless.” Because what I had been told again and again as a girl was that I was useless. That all I could do was marry into a temple, and that studying Buddhism would be pointless. Even in lectures at Komazawa University, some would say such things outright. But this professor was different. He said that Dōgen’s words might indeed be useless, but they would make one’s life beautiful.

When I speak about discrimination in Buddhism, I am often asked: “If that’s how it is, why don’t you just leave Buddhism?” But faith is not like that. Believing does not guarantee any benefit. It does not ensure a peaceful death. And yet, people cannot simply discard their faith. Why is that? When I wrestle with this question, I hear again the professor’s voice: “It may be useless. But it will make your life beautiful.” Because of that, I continued studying under him, and, with his recommendation, I began working at the Sōtō Headquarters in Tokyo. I officially retired two years ago, but I am still working there as a contract staff member. For over thirty years now, I have also been active as a Buddhist feminist, writing and speaking through groups such as the Tokai-Kanto Network of Women and Buddhism and the AYUS International Buddhist Cooperation Network where Ms. Mika Edaki, who is here today, currently serves as director.

Although I was once deeply disillusioned with temple life, I still love Dōgen’s teachings and I still love Buddhism. It is often said Buddhism is discriminatory in terms of gender, but I think this is because Japanese Buddhism became intertwined with the family system through the parishioner system (檀家制度 danka seido), established in the Edo period, and grave-keeping practices. In aligning itself with the values of the medieval household system, Buddhism reinforced patriarchy. It was not that Buddhism itself was originally discriminatory but that in adapting to society and its expectations, it became so.

The fortunate thing is that the traditional family system is now collapsing. Parishioners are leaving temples, and traditional Buddhist institutions are beginning to recognize that if they continue treating women as inferior, they may not survive. Social change is forcing temples to change as well. Yet the mindset of monks still lags behind. Some say, “Now that we recognize gender equality, let’s get women more involved so they can be useful to the temple.” But that is not the point. The real issue is not whether women are “useful” or “not useful.” My professor’s words surpass all of that: “But it will make your life beautiful.” That beauty is not about being male or female. It is about who you are, beyond such categories. As a feminist, I feel grateful that I encountered Buddhism in this way, and I hope that my encounter with all of you today will also be a good one.

May the merit of this gathering extend to all beings, so that together we may walk the Buddha’s path.

Gasshō (with palms joined).

日本の仏教界のジェンダー

最初に言っておきたいのは、私の所属する禅宗の一派、曹洞宗には、本来なら性差別的な教えはまったくないということです。開祖道元は、日本の山岳信仰の聖地などにある「女人禁制」を厳しく批判しているくらいなので、ことさら女性を下に見ていたわけではありません。しかし、現実には他の伝統仏教教団と同じくとても性差別的な男社会であり、女性を一段低くみている。それはなぜなのか。今日は私が体験したふたつのエピソードをとおして、この問題についてお話ししたいと思います。

私は三重県という、地方のお寺の住職の娘として生まれました。

ご存じだと思いますが、日本の伝統仏教教団の男性僧侶というのは、結婚してお寺に家族といっしょに住んでいるのが一般的です。そして、自分の子どもにお寺の跡を継がせます。私が生まれそだったのは、お寺からの収入だけでは生活が成り立たないような小さなお寺でしたけれども、それでも私はお坊さんになりたくて、十歳のときに、住職である父に「お坊さんになりたい」と言ったんですね。ところがそれを父が断ったんです。何と言って断ったかというと、「女が継ぐと寺の格が下がる」と言って断った。

これは私にとっては、とってもショックな出来ごとでした。性差別という言葉はまだ知らなかったかもしれませんが、とんでもなく失望したわけです。なぜ女がやると、格が下がるのか。

この話を、日本の仏教関係者、お坊さんにすると、だいたいこう言われるんです。「それは、君がお坊さんになると苦労するからそう言って断ったんだよ」と。「それは、お父さんの愛だよ」と。それで私はまた、失望するんです。

だって、私がもし男の子だったら、お坊さんになりたいと言ったらみんな大喜びするはずなんですよ。現在、曹洞宗のお坊さんになっているのは九割以上がお寺に生まれた男の子たちです。それなのになぜ、女の子はだめなのか。それは、女性のお坊さんを下に見ているからですね。いくら頑張っても、女性の僧侶は男性の僧侶に劣る。だから反対する。でも、それが愛ですか?

でもですね。この話を、外国で仏教を研究しているとか、在家の仏教者として活動している女性にしたら、反応が全然違ったんです。「なんてひどいことを!」「それは、ショックだったでしょう」と言って、同じように悲しんで、わかってくれるんです、私の気持ちを。そのときはとても嬉しかったです。

なぜ、こんなにも反応が違うんだろうと考えたとき、日本の仏教関係者の反応というのはつまり、私が何を望んでいたかなんてことは、どうでもいいんです。住職である父の判断が絶対に正しいんだから、それに従え。それが「愛」なんだ、ということなんです。女性は男性の言うことに従うべきだ。男性は女性を導く立場にあるんだから、という思い上がりが、そもそも日本の伝統仏教における性差別を生み出しているんではないのかな、と私は思います。

しかも、このとき父が言った、「女が継ぐと寺の格が下がる」なんてことは、まったくのでたらめだったんです。それがわかったのは、ずいぶん後のことですし、お話していると長くなるので今はやめておきます。

それでは、ふたつめのエピソードについてお話しましょう。

そんなふうに、お寺についてはまったく失望してしまった私ですが、何とかして東京に出てきたかったので、曹洞宗の大学なら行っても良いと言われましたので、駒澤大学に進学したんですね。そこで、本格的に曹洞宗の教えについて学ぶことになりました。

二十歳のときでした。開祖道元が書いた『正法眼蔵』っていう本の講義を受けていたとき、同級生が先生に質問した、というよりは食ってかかったんです。「こんなの読んで何になるんです。寺に帰ったら(と、いうことは彼もお寺の息子だったわけですが)毎日葬式法事で、読むのは意味のわからないお経ばっかりだ。こんなの、何の役にも立たないじゃないですか!」って。

そのとき先生が言われた言葉を、四○年以上経った今も、はっきりと覚えています。「そうだね」と、先生はおっしゃいました。「何の役にも立たないかもしれないが、これは君の一生を美しくするんだよ」と。

この話をよそでした時に、聞いていた人に「仏教は人生を美しくするんですね」「感動しました」って言ってもらったんですけれども。私としては先生のこの言葉は、その前の「何の役にも立たない」とセットになっているんです。

つまり、それまで私がさんざん言われてきたのは、女の子は役に立たない、ということだったんです。女の子にはお寺に嫁に行くことくらいしか出来ないんだから、仏教を学んでもむだなんだよ、と。同じ駒澤大学の講義でも、そういうことを堂々と言う人もいましたしね。けれども、その先生は違った。道元の言ったことは、「何の役にも立たないかもしれない」が「一生を美しくする」んだとおっしゃったんです。

よく、仏教の性差別について議論していたりすると、「だったらなぜ、仏教を離れないんですか」と質問されたりすることがあります。でもそれは、次元の違う問題なんです。信仰って、信じたからって、それでなにか得をするわけでもない。安らかに死ねる保証もない。だけど、それでも人は信仰を捨てることが出来ない。それはなぜなんだろう? と考えたりする時にですね、やっぱり先生の声が蘇ってきます。

私はそれで、その先生について学んで、その先生の推薦で、曹洞宗の包括法人事務所、曹洞宗宗務庁というところに就職しました。おととし定年で退職しましたが、今は嘱託職員として働いています。三〇年くらい前からフェミニストの仏教徒として、「女性と仏教・関東ネットワーク」や、ここにおいでの枝木美香さんが現在事務局長をしている「アーユス仏教国際協力ネットワーク」で、文章を書いたりお話したりしています。

いったんはお寺に失望した私ですが、今でもやっぱり道元の教えが好きだし、仏教が好きですね。

「仏教は性差別的だ」とよく言われます。でもそれは、日本の仏教が、檀家制度やお墓の制度によって家制度と結びついて、家父長制の価値観を強固にする手助けをしてきたからだと思うんです。仏教がもともと性差別的だったのではなくて、社会制度と結びついたことによって、あるいはその社会に受け入れられやすい言説を使うようになったことで、性差別的になっていったんじゃないか、と。

でも。ありがたいことに、最近ではその家制度の方が崩壊してきてしまっています。檀家さんがどんどん離れてしまって、このまま女性を軽んじる対応を続けていたら、お寺は存続できないということも、伝統仏教教団の人たちは、たぶんわかってきていると思います。これも、社会の変化によって、お寺も変わらざるを得ないということひとつです。

ただ、それでもお坊さんたちの感覚はまだまだ遅れていますね。男女平等なんだから、もっともっと女の人に、お寺の役に立ってもらおうというようなことを言う人もいますが、私たちが言いたいのは、そういうことではないんです。

役に立つか、立たないかではないんです。「ここに美しいものがあるんだ」という、先生の言葉は、そんなこと超えているんです。自分はどうだ、と。男だ女だ、そんなこと関係ないんだ、と。

私はフェミニストとして、仏教と良い出会い方をしたと思います。今日のみなさまとの出会いも、どうか良いものになりますように。

願わくばこの功徳をもって一切に及ぼし

我らと衆生とみなともに仏道を成ぜんことを 合掌