An Engaged Buddhist History of Japan from the Ancient to the Modern

March-August 2024

go to Volume II August-December 2024

Explore some of the fascinating comments and insights by various authors and Socially Engaged Buddhists in Japan that appear throughout both volumes!

At the End of the 20th Century & Towards a Postmodern Japanese Social Ethics Informed by Socially Engaged Buddhism

“As the collective euphoria of the economic boom began to wane in the 1980s and 90s and there arose some doubt about a morality based on collective utilitarianism, a new type of religious morality began to appear. Since the 2000s, an increasing interest in Socially Engaged Buddhism began to emerge not so much among the common citizens but more within the Buddhist world. Temples have come to see that their old-fashioned way of community activities is not enough and have begun to reach out to wider society by engaging in a variety of activities from disaster relief, suicide prevention, and so forth. As the very communalistic non-individualistic society linked to a hierarchical authoritarian state has come to be less and less acceptable to people, they have started to look for a new source of morality and ethics. As such, one based in Buddhism seems to be on the rise. I remain hopeful that this new Buddhist morality will be more expansive and universal and might lead to a kind of ‘autonomous Buddhist social ethics’ (自律的な仏教社会倫理 jiritsu-teki Bukkyo shakai-rinri).” – Shimazono Susumu, Professor Emeritus, Tokyo University and leading scholar on postwar Japanese religion. Volume I, p. 300.

“In a society with a democratic orientation, however, Buddhism would actively recognize the existence of other religions and non-religions, accepting them as one in a pluralistic range of thought and religion, and, as such, embodying Buddhism in society. This means recognizing freedom of religion and separation of church and state (the non-monopolization of authority by a single religion) as well as developing the concept of embodying Buddhist ideals and ideas in the public space while spreading them throughout society. The idea is that a public religion should have a religious foundation but can only speak out and act in a democratic society where diverse ideas coexist. In this way, the social ethics of religion can be transmitted into the world…. While secularization has caused one aspect of religion’s influence to recede, it has also given rise to the possibility that religions that are aware of their role as public religions will increase their influence.” – Shimazono Susumu, Professor Emeritus, Tokyo University and leading scholar on postwar Japanese religion. Volume I, p. 311. Translated from Social Ethics in Modern Japanese Buddhism: Living by “True Dharma” (近代日本仏教の社会倫理:正法を生きる Kindai Nihon Bukkyo-no shakai-rinri: Shobo-wo-ikiru). (Tokyo: Iwanami-shoten 岩波書店, 2022)

1970s & 80s: Japanese Buddhist NGOs, Southern Asia & Global Civil Society

“We have to look back carefully to our relationships with the other ethnic groups of Asia, like the Chinese, Korean, Thai, etc. from the Nara era and before that to the Jomon (14,000–300 BCE) and Yayoi (300 BCE–300 CE) periods. This legacy must be carefully studied. If we don’t reconstruct our relationships with these other Asian peoples, we have no future. In short, Japanese are useless without the intellectual support from Korea and China. Almost all major streams of Japanese Buddhism came from Korea and China. Sometimes we have lost a sense of this background. We have to make an effort to rebuild these original relationships and only then can we find our new horizon.” – Nakamura Hisashi 中村尚司, Professor Emeritus Ryukoku University affiliated with the Jodo Shin Hongan-ji Pure Land denomination and leading development economist

“The change that is needed to bring a halt to this ailing local Japanese society is to become part of ‘global civil society’ through building solidarity between South and North. I wonder if we can voluntarily create a global society of equality based on new values. Working together means that you and others must always be equal or co-equal, that generosity and helpfulness must not be accompanied by conceit or superiority over others, and that you must always think and act from the same perspective as the other person.” – Rev. Arima Jitsujo 有馬実成 (1936-2000), founder of the Japan Soto Zen Relief Committee (JSRC). Volume I, p. 275.

“For civil society to thrive, it must be based on something more than the pursuit of individual self-interest, on something more than intermediate associations that work to limit state power. The widespread assumption that civil society is a morally-indifferent sphere of self-interested cooperation, and that the common good is merely a sum of our private goods, must be questioned. This is something religions are well-placed to do, for it is their role to offer alternative explanations of what our lack is and how to address it. In my contemporary Buddhist terms, civil society must again be recognized as that dimension of our lives where we work together to reform society so that it does not objectify greed, ill-will. and ignorance in institutions, but instead empowers us to understand and address our lack.” David R. Loy, Sanbo Kyodan Zen order and author of A Buddhist History of the West. Volume I, p. 309.

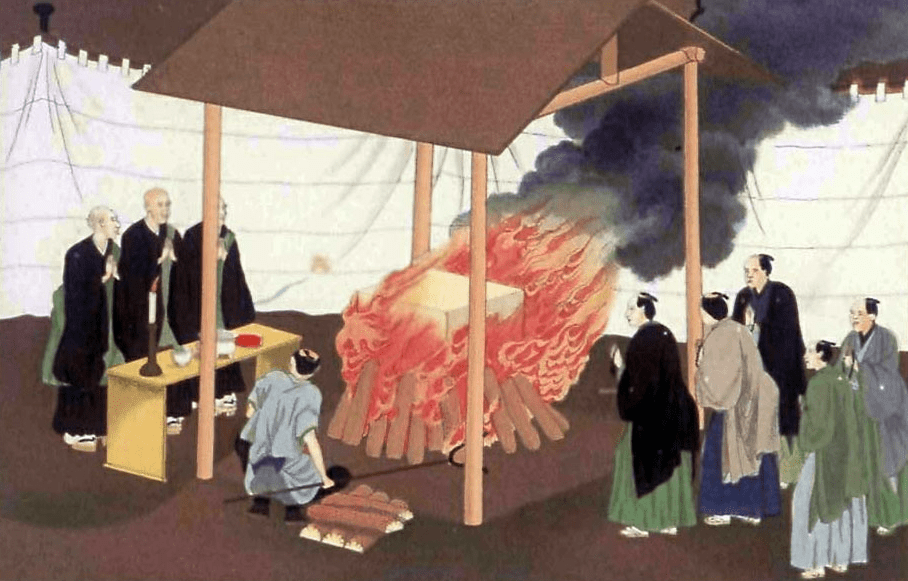

1960s: The Problem of Funeral Buddhism

“Contemporary Japanese Buddhism finds itself deeply mired in an identity crisis that is the fruit of its ongoing negotiation with modernity since Japan opened its borders to the West in the mid 19th century. The changing demographic landscape of modern Japanese society has increasingly marginalized Buddhist temples and priests from their central roles in the nexus of traditional, rural community life. In the mass shift of the population to urban eras after World War II, many Japanese abandoned their traditional family temples in the countryside. While there have been a number of attempts at internal reform and restructuring, few of these efforts have led to any substantive change in the nature of traditional Japanese Buddhism, which maintains its style of ancestor veneration around funerals and memorial services, or what is now pejoratively dubbed as Funeral Buddhism (葬式仏教 soshiki bukkyo). It is not known by whom the term was first coined, but it became popular in public discourse in the 1960s with the publication of the book Funeral Buddhism by Tamamuro Taijo 圭室諦成, a professor at Meiji University. The period of rapid economic growth into the 1980s exacerbated this trend. Priests became known for their consumptive appetites for sports cars and golfing, and another pejorative term bozu-marumoke, ‘money grubbing ritualist’, was coined.” Volume I, pp. 12-15.

“What is common to the Buddhist stance in both periods [the subsequent Tokugawa and Meiji periods] was neither outright defeat nor spiritual autonomy, but, in fact, Buddhism’s surrender, a submission to a relationship of mutual dependence in which Buddhism held the subordinate position. I believe we must acknowledge how oppressive this matter has been in the history of Japanese Buddhism—a central problem from which there has been no liberation.” Volume I, pp. 96-97.

[In the Tokugawa Era 1603-1868] “Buddhism, bereft of its original logic and depth of belief, became a hollow, popularized version of itself that proposed a generally easy realization of Buddhahood after death, leaving it little alternative than to turn into ‘funeral Buddhism’; this amounted to the subordination of religion to politics. The soul that attains Buddhahood (成仏 jobutsu) after death must be seen as in a far lower spiritual state than that of a person who achieves jobutsu in its original sense of becoming an awakened being and realizing the dharma. This was not a manifestation of respect towards the dead; it was, rather, nothing but a false consciousness created by the political exploitation of religion.” – Kuroda Toshio 黒田俊雄 (1926-1993), Professor Emeritus, Osaka University, renowned expert in medieval Japanese history. Volume I, p. 106.

Socially Engaged Buddhism in Postwar Japan

“Japan is the only nation in the world which has experienced the dread of nuclear weapons. Japan is also the first country in the world that has adopted a constitution of absolute pacifism … We want to stress, therefore, that Japan is entirely qualified to be in the vanguard, to mobilize all the peace forces of the world, to assume the leadership, and to rouse world opinion through the United Nations.” – Ikeda Daisaku 池田大作 (1928-2023) the third-generation leader of the Nichiren lay denomination Soka Gakkai. Volume I, p. 245.

“Out of the tradition of Hinduism, there emerged Buddhism, which embodies the idea of non-violence in its most complete form. Buddhism is not only necessary for promoting a peaceful revolution in today’s India but also is a tool of spiritual guidance with which to save all the human race who are involved in acts of violence and wars; it encourages abolition of all means of violence. My wish for ‘the compassionate return of buddhas and bodhisattva to this world’ (還来帰家 genrai-ki-ke) and the non-violent revolution which Gandhi advocated came from the same origin, the doctrine of Buddhism. This concept cannot be fully expressed in the term ‘revolution’, and in Buddhism it is referred to as ‘attainment of Buddhahood’. The ultimate revolutionary aim of Buddhism consists in having both man and the world attain Buddhahood. Completely detached from things like political power, the human race should leap above all such conflicts. This is the true essence of Buddhist revolution.” – Ven. Fujii Nichidatsu 藤井日蓮 (1885–1985) founder of the Nipponzan Myoho-ji Buddhist order. Volume I, p. 212.

“If one does a variety of things in addition to a religious movement, each will fail. That’s because there is no mirror to illuminate. Religion establishes something like Buddha or God. That teaching becomes a mirror. Politics wanders here and there. There is no mirror. One will be pulled both ways. This results in things like power acquisition or vote collection.” – Ven. Fujii Nichidatsu 藤井日蓮 (1885–1985) founder of the Nipponzan Myoho-ji Buddhist order. Volume I, p. 296.

“Although Buddhism has been the flesh and blood of Japanese culture for more than the past ten centuries, the people by and large still regard it as ‘an imported system of thought’. In this respect, our attitude differs from those of Western nations in regard to Christianity and from those of southern Asiatic nations in regard to Buddhism. As for those nations, universal world religions are conceived to be such integral parts of their own culture that they are linked to the formation of respective norms themselves. But for the Japanese, in contrast, such a conception is totally absent.” – Nakamura Hajime, world-renowned Japanese scholar of Vedic, Hindu, and Buddhist texts. Volume I, p. 20.

“While traditional East Asian Mahayana Buddhism lay in the ruins of the war and the communist revolutions in China and Korea, the immediate postwar era was one of great dynamism in South and Southeast Asia for principled social change, the articulation of a non-aligned Asian modernity, and Socially Engaged Buddhism. In noting the lack of dynamic, principled Socially Engaged Buddhism in Japan in the postwar era, it seems the traumatic effect of the war on Japanese Buddhism cannot be overestimated. What remains striking is how little influence these alternative Buddhist visions of Asian modernity have had in Japan compared with liberal and socialist visions as well as archaic Japanese ones that continue to predominate Japanese public discourse.” Volume I, pp. 222-23.

Religion in Postwar Japan

“Even the new religions, the primary expression of postwar Japanese spirituality, emphasize personal and group prosperity and the morality of group cohesion rather than any more transcendental ethical injunctions.” – Robert Bellah, Professor Emeritus, University of California at Berkeley and author of Tokugawa Religion: The Cultural Roots of Modern Japan. Vol. I, p. 241.

“Postwar Japan was swept up in this feeling of succeeding as a group through ‘collective utilitarianism’ (集団功利主義 shudan kori-shugi) and so called ‘Japanese corporate management’. This euphoria let us forget the bitter experience of WWII and bask in the glow of this economic miracle. The new religions, such as Soka Gakkai, also resonated with these trends. They helped provide a new object of veneration in their charismatic leaders to replace the void left by the emperor’s retreat. This also allowed people to not reflect on the failures of the war.” – Shimazono Susumu 島園進, Professor Emeritus, Tokyo University and leading scholar on postwar Japanese religion. Vol. I, p. 251.

Dissenting Voices & Debating the Source of Social Ethics in Early Postwar Japan

“The five peace principles (of the Non-Aligned Movement) mark a new stage in the history of the development of democracy. Until now democracy was exclusively a principle related to a country’s internal politics, and it was problematic to use it to control relations between states. Especially in the case of Western countries where democracy was developed early, because these countries were at the same time using Asian and African regions as colonies, democracy had a false reputation in the context of relations between Asia, Africa, and the West…. If we think about the significance of these five principles, it must be seen as only natural that these principles, differing from the great principles and theories to date, were created not in Washington, Paris, or Moscow, but in a corner in Asia.” – Shimizu Ikutaro 清水幾太郎 (1907–1988), prominent postwar social critic and activist. Vol. I, p. 229-30.

“Just as before, mass nationalism in Japan is the reverse side of the mirror of Japanese capitalism, which exists with the Imperial family living like a ghost in its shadow. Mass nationalism shows its own mirror to the ruling class, with its passion for peep shows and its respect for the directors of companies and its vague yearnings and feelings for nature and its symbols of popularity. The way to naturalize this mass nationalism politically is to drive the capitalist class itself into a corner and push it over the edge, and in the realm of ideas, the masses themselves, be deepening their living thought and making it more independent, will cause themselves to become more separate. Then both images will be turned upside down: the image of the citizens’ (shimin) unification according to the nationalism as defined by postwar intellectuals, and the image of false socialism as defined by the postwar ‘internationalists’. This idea can be called ‘independence’; but it is not a matter of name but of reality. To walk without compromise will be long and difficult.” – Yoshimoto Takaaki 吉本隆明 (1924–2012), anti-intellectual public intellectual & one of the leaders of the 1960s student movement. Volume I, p. 233. Quote from Olson, Lawrence. “Intellectuals and ‘The People’: On Yoshimoto Takaaki”. The Journal of Japanese Studies. Summer, 1978. Vol. 4, No. 2, p. 348.

“From a way of thinking which makes absolute that which is particular, there will never emerge from within oneself the way of thinking which is able totally to transform the self.” – Maruyama Masao 丸山眞男 (1914–1996), leading postwar political scientist and public intellectual. Vol. I, p. 228.

“Those who observed the moral confusion in Japan immediately after World War II may be led to doubt the proposition that the Japanese in the past were moralistically inclined. Little difference seems to be discoverable between traditional and recent Japanese morality. The difference seems to lie rather in the fact that what was considered to be morally tenable in Japan’s ‘closed-door’ past became untenable under rapidly changing worldwide social and economic conditions to which Japan is adapting itself. The traditional concept of honesty as loyalty to the clan and Emperor is applicable only to the conduct of man as a member of the particular and limited human nexus to which he belongs; it is not applicable to the conduct of man as a member of human society as a whole.” – Nakamura Hajime, world-renowned Japanese scholar of Vedic, Hindu, and Buddhist texts. Volume I, pp. 18-19.

“All the work to which I have devoted myself has failed … I am ashamed of my own ‘recanting and converting’ (tenko). I should have not refused to die in prison … My cowardice and meanness were pitiful. For that, I have lost my eternal soul … I no longer see Buddhism as my ideology. There is no choice but for me to serve my brothers and sisters as a Marxist in the years left to me.” – Seno-o Giro 妹尾義郎 (1889–1961), Nichiren priest & prewar/postwar social activist. Volume I, p. 219.

“From that time, the question arose among us of what is it good to live for now? Amidst debates with friends who held these same sentiments, we ourselves came to understand about the militaristic education that we were raised in. Then we had to change to a world in which democracy was considered the right thing. During the war, I had a teacher who pushed me very strongly into militarism. After the war, he said, ‘From now on, this is the age of democracy.’ He then repeated to me in English Abraham Lincoln’s famous words, ‘Government of the people, [by the people, for the people].’ This same teacher during the war had said, ‘After we win the war, Americans will also come to speak Japanese.’ In this way, we came to be unable to trust our teachers and other adults. I thought to myself, ‘Will the center of the world change again? Is there a way to live that doesn’t fall victim to the vicissitudes of change?’” Master Kono Taitsu 河野太通老師, Chief Priest of the Rinzai Zen Myoshin-ji order 臨済宗妙心寺派管長 2010-14, Chairman of the Japan Buddhist Federation 全日本仏教会会長 2010-12. Volume I, p. 200.

“All of Japan’s Buddhist sects flipped around as smoothly as one turns one’s hand and proceeded to ring the bells of peace. The leaders of Japan’s Buddhist sects had been among the leaders of the country who had egged us on by uttering big words about the righteousness [of the war]. Now, however, these same leaders acted shamelessly, thinking nothing of it.” – Rev. Yanagida Seizan 柳田聖山 (1922–2006) Rinzai Zen priest & Director of the Institute for Humanistic Studies at Kyoto University. Volume I p. 200.

“During discussions held with Society [Soka Gakkai] members both collectively and individually, I have often had occasion to discuss His Majesty. At that time, I pointed out that His Majesty, too, is an unenlightened being (bonpu) who as Crown Prince attended Gakushuin (Peers’ school) to learn the art of being emperor. Therefore, His Majesty is not free of error…Were His Majesty to become a believer in the Supra-eternal Buddha (久遠本仏 Ku-on-honbutsu) [of the Lotus Sutra], then I think he would naturally acquire wisdom and conduct political affairs without error.” – Makiguchi Tsunesaburo 牧口常三郎 (1871–1944), founder of Soka Gakkai, Japan’s largest postwar new Buddhist denomination. Makiguchi was imprisoned for such commentary, and refusing to “recant and convert” (転向 tenko), he died in prison during the war. Volume I pp. 201-11.

The Militarization of Japanese Buddhism

“The state is the power that creates value. The true state must, as the subject of historical formation, be the creator of value. What is called national value is creative value. For this reason, it is true moral value. In the background the state possesses something religious: the national polity in which ‘the state, just as it is, is morality’ (国家即道徳 kokka-soku-dotoku).” Nishida Kitaro 西田幾多郎 (1870–1945), prominent prewar Zen intellectual and founder of the Kyoto School 京都学派. Volume I pp. 192-93.

“Whether one kills or does not kill, the precept forbidding killing [is preserved]. It is the precept forbidding killing that wields the sword. It is the precept that throws the bomb.” Master Sawaki Kodo 澤木興道 (1880–1965), prominent Soto Zen priest of the pre and postwar eras. In Volume I p. 186.

Sawaki Kodo’s re-expression of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Vows

Sentient beings are numberless, I vow to liberate them. 衆生無辺誓願度

Delusions are inexhaustible, I vow to eliminate them. 煩悩無尽誓願断 becomes Enemies of the Court are inexhaustible, I vow to eliminate them. 朝敵無尽誓願断

Dharma doors are infinite, I vow to master them. 法門無量誓願学

The Buddha Way is unsurpassed, I vow to attain it. 皇道無上誓願成 becomes

The Imperial Way is unsurpassed, I vow to attain it. 皇道無上誓願成

“Hongaku 本覚 [original enlightenment] thought is represented as an uncritical affirmation of reality that, in regarding all phenomena as expressions of original enlightenment, endorses things just as they are. In arguing the nonduality of good and evil and legitimating all phenomena, even human delusion, as original enlightenment, medieval hongaku thought exerted an antinomian influence, denying the necessity of religious discipline, undermining the moral force of the precepts, and contributing to clerical degeneracy. The ‘world affirming’ tendency of medieval hongaku thought has [also] been interpreted as an authoritarian discourse that legitimated social hierarchy and the entrenched system of rule.” – Jacqueline I. Stone, Professor Emeritus, Princeton University and author of Original Enlightenment and the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism. In Volume I p. 51.

“Japanese society has never firmly established a class comparable to the literati in China or to the caste of Brahmin priests in India. It cannot be said that the socio-economic situation in Japan prevented such a class from emerging. It was rather the Japanese inclination to emphasize the order of human nexus that enabled the soldiers, whose essential function was the use of force, to rise to high positions as the rulers of the society.” Volume I, p. 81.

“We find only a few cases in which sacrifices of life were made by the Japanese for the sake of something universal, something that transcends a particular human nexus, such as academic truth or the arts. And if we exclude the persecutions of the True Pure Land [Jodo Shin] sect, the Hokke [Nichiren] sect, and Christianity, cases of dying for religious faith are exceptional phenomena. Sacrifice of all for the sake of truth, when it went contrary to the intentions of the ruler, was even regarded as evil.” – Nakamura Hajime, world-renowned Japanese scholar of Vedic, Hindu, and Buddhist texts. Volume I, p. 92.

Attempts to Reconcile Buddhism, traditional Japanese thought, Western Liberalism & Marxist-socialism

“Just as the Japanese are apt to accept external and objective nature as it is, so they are inclined to accept man’s natural desires and sentiments as they are, and not to strive to repress or fight against them…. Naturalism in the sense of satisfying man’s desires and sentiments, instead, was a predominant trend in Japanese Buddhism.” – Nakamura Hajime, world-renowned Japanese scholar of Vedic, Hindu, and Buddhist texts. Volume I, p. 175.

“Buddhists aim to penetrate deeply to the inner Nature, the spiritual Nature, the Nature which is the Law of Nature, which is the source of everything…. If we realize this Nature, we have no way that selfishness can happen.” – Buddhadasa Bhikkhu (1906-93), renowned Thai Theravada reformer. Volume I, p. 177.

“The basis of the three-thousand-year history of the Japanese Empire is essentially different from Western history. Modern Western materialism is so far different from Japan’s tradition. In the West, society is the basic datum, but for the Japanese, the state is the basic datum. Liberalism, communism, and individualism, which are more or less anti-state fundamentally, cannot possibly occupy a basic position in Japan. The national spirit of Japan—which is cheerful, cooperative, and loves symmetry and harmony—could not long endure the lowly people’s spirit that moves through individual benefits, struggle/conflict, and hatred and envy. If we adopt the self-consciousness of the Western European individual and reintegrate into this, then we can show to the world a new social form that Western Europeans must consider…. Buddhism is not content only with a superficial institutional resolution [of the problem of ‘exploitation’],as is ordinary socialism, but endeavors to resolve [it] in relation to a revolution in human nature.” – Sano Manabu 佐野学 (1892-1953), co-founder of the Japanese Community Party in 1922, Volume I, p. 173.

“A political theory that posits men as atomistic individuals is unlikely to be received in the Japanese context without undergoing transmutations that make it more compatible with an indigenous perspective in which selfhood has meaning only in the context of intersubjectivity within community. As contextuals, Japanese liberals were disposed to attribute moral value to the community, hence to the state, an organic (as opposed to contractarian) conception of which was closely bound to the idea of the nation in Meiji and pre-Meiji political thought. It is not surprising, then, that virtually no Meiji or Taisho liberals should have subscribed to an individualist variant of classical liberalism in preference to privileging the state as a kind of moral community. The weakness of these Japanese liberals lay not in their collectivism, but in their traditionalist conflation of nation and state. A liberalism founded on an abstract conception of natural rights vested in atomistic egos could no more diminish their pain than the equally alien and traumatic conception of class struggle espoused by Marxists. With the advent of war, their liberalism, as Japanese liberalism,had to accommodate disparate notions of self and modernity that ultimately came into such intense conflict that it was either extinguished or transmuted into its opposite.” – Germaine A. Hoston, Professor of Political Science at the University of California, San Diego and author of Marxism and the Crisis of Development in Prewar Japan. Volume I, p. 169.

“As a propagator of Buddhism I teach that ‘all sentient beings possess Buddha nature’ (一切衆生悉有仏性 issai shujo shitsu bussho) and that ‘within this Dharma there is equality, with neither superior nor inferior’ (此法平等無高下 kore-ho byodo mu-ko-ge). Furthermore, I teach that ‘all sentient beings are my children’ (一切衆生的(皆)是吾子 issai shujo mina kore ako). Having taken these golden words as the basis of my faith, I discovered that they are in complete agreement with the principles of socialism. It was thus that I became a believer in socialism.” Uchiyama Gudo 内山愚童 (1874–1911), Soto Zen priest and propagator of “anarcho-communist revolution” (無政府共産革命 mu-seifu kyosan kakumei). Uchiyama was executed as part of the High Treason Incident (大逆事件 Taigyaku Jiken), also known as the Kotoku Incident (幸徳事件 Kōtoku Jiken), a socialist-anarchist plot to assassinate Emperor Meiji in 1910. Quote from Shields, James Mark. Against Harmony: Progressive and Radical Buddhism in Modern Japan. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 160.

“For postwar Buddhist social critic Nakamura Hisashi 中村尚司, the marginalization of Buddhism from mainstream society in the early modern era in Japan pushed it towards a kind of social dynamism and saw the emergence of a variety of public Buddhist intellectuals and even social activists—whom we can consider Socially Engaged Buddhists—that was so lacking in the latter half of the century after World War II. James Shields in his excellent work Against Harmony: Progressive and Radical Buddhism in Modern profiles the participants of the Meiji Buddhist Enlightenment (仏教啓蒙活動 Bukkyo Keimokatsudo) movement of the 1880s and 90s and its successor the New Buddhist Movement (新仏教運動 Shin Bukkyoundo) of the 1900s and 10s, which included Suzuki Daisetsu 鈴木大拙. He explains how they sought a Buddhism that was a global, cosmopolitan philosophy fitting for the modern, industrial, and democratic state, yet also able to serve the people and the nation in times of crisis. In this way, however, many of them remained loyal to the emperor and saw the state as the protector of the people against foreign imperialism—sensibilities that mirrored those of the urban, elite liberals of this period. These blind spots led many in the movement to slide into the nationalistic and totalitarian discourses that emerged in Imperial Japan. In this way, Shields summarizes the movements as ‘an overly intellectual perspective rooted in middle-class and liberal assumptions—aspects that prevented it from emerging as a truly viable alternative for Buddhists in either the pre- or postwar eras.’” Volume I, p. 153.

Engaged Buddhist Voices in Early Modern Japan

“There are signs of a gradual increase in the number of social programs in our country, which are being organized to meet the needs of society. While this is an inevitable trend in view of the development of the nation’s destiny, it is a very welcome one from a general point of view. However, are the various charities that are now flourishing based on a solid foundation and a certain policy? Or are they just starting out, driven by the demands of the state and society, “without any principles or policies” (mu-shugi mu-koshin)? Perhaps the spirit is truly admirable, but the effort is not worth it because of a lack of regard for “the progress of the times and the appropriate means and methods” (jidai-no shinpo-ya teki-to-no hoho shudan). In any case, I would like to ask what kind of principles are at the root of today’s Sensitization and Relief Project (感化救済事業 Kan-ka kyu-sai ji-gyo)? What is the policy that is derived from this principle?” – Rev. Watanabe Kaikyoku 渡辺海旭 (1872–1933), Jodo Pure Land priest & pioneer in the modern social welfare movement

“I simply seek that the distinction between doctrines of rule (chikyo) and religion (shukyo) be made clear. I ask the incorporation of useful law derived from foreign nations, the study of beneficial sciences, and the use of electricity and steam powered vehicles and the like, not to be interpreted as the fulfillment of mysterious and divine orders, as the brilliance and munificence of a divine rule, or as the glorious manifestation of a religion of the hidden. These abilities are all none other than the result of efforts made to expand and lengthen ‘the great road of civilization’ (bunmei-no dai-do).” – Rev. Shimaji Mokurai 島地黙雷 (1838–1911), Jodo Shin Pure Land Hongan-ji priest & leader in the Meiji Buddhist Enlightenment from Shields, James Mark. Against Harmony: Progressive and Radical Buddhism in Modern Japan. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 129.

Counter Trends & De-Axialization in Modern Japan

“This hardly means, however, that Japanese Buddhism was immoral or amoral. Monks and faithful alike observed assiduously the requirements of their limited human nexus; they were highly moral in this respect. They were devoted to their parents and loyal to their sovereign. They were in every respect quite different from the monks and novices of India and China. Moreover, Japanese monks were devoted workers loyal to the interests of the order to which they belonged. If the followers of one sect founder are divided into a number of different orders, monks in one of the orders become devoted to his particular order to the point of boycotting the other orders. To them the welfare of their small separate orders are their main concern and the doctrine to which they all adhere is reduced to a secondary concern. Here again they are moral in the limited sense that they are devoted to their limited human nexus. The precepts to be kept by an individual as an individual in relation to the Absolute, by an individual in relation to another individual qua individual tend thus to become neglected. The interests of their own small limited nexus become the factors determining their actions.” – Nakamura Hajime, world-renowned Japanese scholar of Vedic, Hindu, and Buddhist texts. Volume I, p. 56.

“In 1872, the new Meiji government issued a decree deregulating state control over, and enforcement of, the Buddhist monastic vinaya, known as the ‘meat eating and marriage’ (肉食妻帯 nikujiki saitai) policy. In short, it ended all penalties for Buddhist monks who violated state and denominational standards by eating meat, marrying, letting their hair grow, or abandoning monastic robes at any time. This regulation and its aftermath represents the logical conclusion of the immanentalization of the Buddhist monk in Japan: beginning with the lay bodhisattva values espoused by Prince Shotoku at the opening of the 7th century; which were brought to fruition by Saicho’s abandonment of the classical Dharmagupta Vinaya in favor of the exclusive practice of the Brahma Net Sutra bodhisattva precepts at the opening of the 9th century; which eventually gave birth to the Pure Land movement’s guarantee of salvation without any of the classical monastic trainings of sila-samadhi-prajna and the Jodo Shin sect’s complete abandonment of the monastic vinaya in the 12th and 13th centuries. It is more than ironic that the Pure Land movement, which had been considered a wildly heretical cult and endured numerous persecutions in the Kamakura period, became the standard bearer of these new meat-eating married priests”. Volume I, p. 132.

“There did not develop in Japan the emphasis on a principled discontinuity between different regimes or ‘stages’ of institutional change. Nor did there develop any strong conception of such changes and breaks as constituting steps in the unfolding of historical programs or cosmic plans with possible eschatological implications. In principle, no new modes of legitimization were connected with such changes. The assumed mythical continuity of the imperial symbolism—often fictitious but continuously emphasized—was crucial in this respect. The bases of legitimization—especially those rooted in the symbolism of the emperor—were continuous and could not be dismantled or changed. The epitome of this emphasis on (a reconstructed) continuity could be seen in the totally new construction of the emperor system under the Meiji regime.” – S.N. Eisenstadt, Israeli sociologist and author of Japanese Civilization: A Comparative View. Volume I, p. 23.

The Axial Shapeshifters of Japanese Buddhism

“Sincerely revere the Three Treasures, viz., the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha, which constitute the final ideal of all living beings and the ultimate foundation of all countries. Should any age or any people fail to esteem this truth? There are few people who are really vicious. They will all follow it if adequately instructed. How can the crooked ways of humans be made straight unless we take refuge in the Three Treasures?” – Article 2 of Japan’s first constitution, the Seventeen Article Constitution written by Prince Shotoku 聖徳太子 (574–622) in 604. Volume I, pp. 37-42.

“If you receive an imperial command, it must be obeyed without fail. The sovereign is heaven, and imperial subjects are the earth…. Should the earth seek to overthrow heaven, there will only be destruction.” – Article 3 of Japan’s first constitution, the Seventeen Article Constitution written by Prince Shotoku 聖徳太子 (574–622) in 604. Volume I, pp. 37-42.

“Nichiren 日蓮 (1222-1282), the final of the Kamakura Buddhist revolutionaries, would take the soteriological implications of Honen, Shinran, and Dogen to their logical conclusion by outrightly proclaiming a theology based on the transformation of society and not just the individual. Nichiren fully embraced the doctrine of the Age of the Final Dharma (末法 mappo), and his teaching of the recitation of the daimoku (Namu-myo Ho-ren-ge-kyo 南無妙法蓮華経) begins to look more like the Pure Land recitation of Amitabha Buddha’s name (念仏 nenbutsu), ‘as a practice for ignorant persons of the Final Dharma age that will save them from karmic rebirth in the lower realms of transmigration.’ Indeed, both the Pure Land and Nichiren orders became beacons to the lower classes, women, and social outcastes living in the dark of the violent rivalries of the ruling classes. For Honen, it was the realization of the Pure Land in the next world, while for Nichiren, it was the realization of the Pure Land in this world. In this way, Nichiren, perhaps more than any of the other Kamakura Buddhist masters, fits the definition of axialization by creating a new ontological vision. This vision would resolve the tension of the social and spiritual collapse of the Heian-Kamakura period as the Age of the Final Dharma, replacing it with the higher enlightened order of the Buddha’s Pure Land as realized in the path of the bodhisattva found in the Lotus Sutra. In many ways, it is a complete Buddhist path with a critique of suffering and its causes as per the First and Second Noble Truths, a vision of the Buddha’s Pure Land as in the Third Noble Truth, and finally the practical path of the bodhisattva as per the Fourth Noble Truth.” Volume I, pp. 71-73.

“While Honen and Shinran literally turned Buddhism upside down in their development of a teaching that fit the time and age of the Final Dharma (末法 mappo), Dogen 道元 (1200–1253), could be said to have turned Buddhism inside out in his resolution to the tension between the transcendental drive to transform mind through practice and the engagement in suffering through acceptance of the world. His ability to recapture the practical essence of Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka thought makes him ‘generally considered to have been the greatest Japanese philosophical thinker’. By reading the Mahaparinirvana Sutra as “All sentient beings are buddha-nature” (rather than have), he rejected buddha-nature as a sort of essential dharma or ontological form. This in turn led him to deny the usual duality between practice and realization, writing, “To think that practice and realization are not identical is a non-Buddhist view…practice must be considered to point directly to intrinsic realization.”. This means that it is available to all persons to manifest as sentient beings and not only the privileged domain of highly accomplished masters. Although mappo did not form an important basis of Dogen’s teaching, he maintains the same liberative thrust of Honen and Shinran by collapsing the distinctions between monastic and lay practice and achieving the harmony of realizing the transcendental through a thorough engagement in the world, in this case, the world of the common discursive mind.” Volume I, pp. 69-70.

“The teachings of Shinran 親鸞 (1173-1263), one of Honen’s principle students, seem to flip the teaching of ‘innate enlightenment’ (本覚 hongaku) on its head as not a rationalization of the status quo of those in power but as an empowerment of those with no power, the bonbu 凡夫, and their blessedness and agency to attain salvation ’just as they are’. Instead of being innately enlightened, Pure Land Buddhists are innately deluded and that means they are more fit to realize salvation due to their groundedness in the realities of the suffering world. In this way, Honen and Shinran’s ministries were a radical rejection of the giant edifice of spiritual materialism in the Buddhist tradition with its highly elaborate philosophies, practices, and rituals that had become the private domain of the monastic elite and social elites, such as those of the Heian era, who patronized and had access to them. Honen’s rejection of the foundational core of Buddhism in the Three Trainings of sila-samadhi-prajna and Shinran’s total embrace of this rejection by openly taking a wife and not shaving his head, becoming ‘neither monk nor layman’, was a message to the common person that not only Buddhist conventions did not need to be followed but also social conventions and entrenched forms of authority.” Volume I, p. 68.

“Honen 法然 (1133-1212) proclaimed that the simple recitation of Amitabha’s name (南無阿弥陀仏 namu-amida-butsu), even just ten times, could erase eons of bad karma and gain one entry into Amitabha’s Pure Land at the moment of death. This teaching, however, was not designed as a simplified, inferior version of dharma practice, often given by monks to lay people whom they feel are unable to realize the highest forms of Buddhist practice. Rather, in this Age of the Final Dharma (末法 mappo), the ‘exclusive nenbutsu’ (専修念仏 senju-nenbutsu) was the best and indeed only way of realizing the highest goal of Buddhism, eventual enlightenment after Birth in the Pure Land (往生 ojo) …. Honen’s isolation of this teaching into a single, exclusively focused school of practice marked a spiritual revolution that in many ways was a call to social revolution—a kind of liberation theology for the masses to throw off the domination of the Heian aristocracy and the clan warlords and to seek for their own independence.” Volume I, p. 66-67

The Roots of Socially Engaged Buddhism in Japan

Socially Engaged Buddhism as a response to modernity

“Although there is a perennial aspect to it dating back to the historical Buddha, Socially Engaged Buddhism has been defined, and can be properly circumscribed, as a movement that began in response to the influences and dislocations of Western colonialization and modernization in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.” (Volume I, p. 121)

Axial Shifts in Culture & Civilization

“By axial civilizations, I refer to those civilizations in which new types of ontological visions emerged and were institutionalized. The development and institutionalization of such conceptions of a basic tension, or chasm, between the transcendental and mundane orders gave rise in all these civilizations to attempts to reconstruct the mundane world—human personality and the sociopolitical and economic order—according to the transcendental vision. These ontological conceptions, which first developed among autonomous, relatively unattached ‘intellectuals’ such as prophets or visionaries, were ultimately transformed into the basic ‘hegemonic’ premises of their respective civilizations [and] became institutionalized as the dominant orientations of both the ruling and many secondary elites, fully embodied in their respective centers or subcenters.” – S.N. Eisenstadt (1923-2010), Israeli Sociologist and author of Japanese Civilization: A Comparative View. (Volume I, p. 21)