A New Socially Engaged Buddhism in 21st Century Japan: From Intimate Care to Social Ethics

Explore some of the fascinating comments and insights by various authors and Socially Engaged Buddhists in Japan that appear throughout both volumes!

The Disconnected Society (無縁社会 Mu-En Shakai)

In January 2010, a new term was coined that seemed to best encapsulate not just Japan’s economic decline, or even the growing sense of anomie, but also the deep spiritual crisis facing the country. The Disconnected Society (無縁社会 mu-en shakai) not only encapsulates many of the social ills of Japan (such as suicide, death from overwork, and social withdrawal) but in its etymology also reveals the deep existential crisis of this situation. The term’s roots in fact lie in Japan’s Buddhist culture. En refers to the teaching of the deep interconnectedness of all phenomena. It can be combined with various other Chinese characters to form a constellation of related Buddhist terms, such as en-gi 縁起 “the principle of dependent origination” (Skt. pratitya samutpada); go-en ご縁 the mysterious or destined “karmic connection” two people may share in this life or over many lifetimes; and the term mu-en 無縁, literally the “lack” or “non-existence” of karmic connection. In Japanese Buddhism, mu-en is used to denote a person who after death has no surviving relatives or loved ones to engage in the ancestral rites of the hybrid Confucian-Buddhist religiosity of most Japanese. In short, this is the Japanese sense of being condemned to hell. Volume II, p. 13-14.

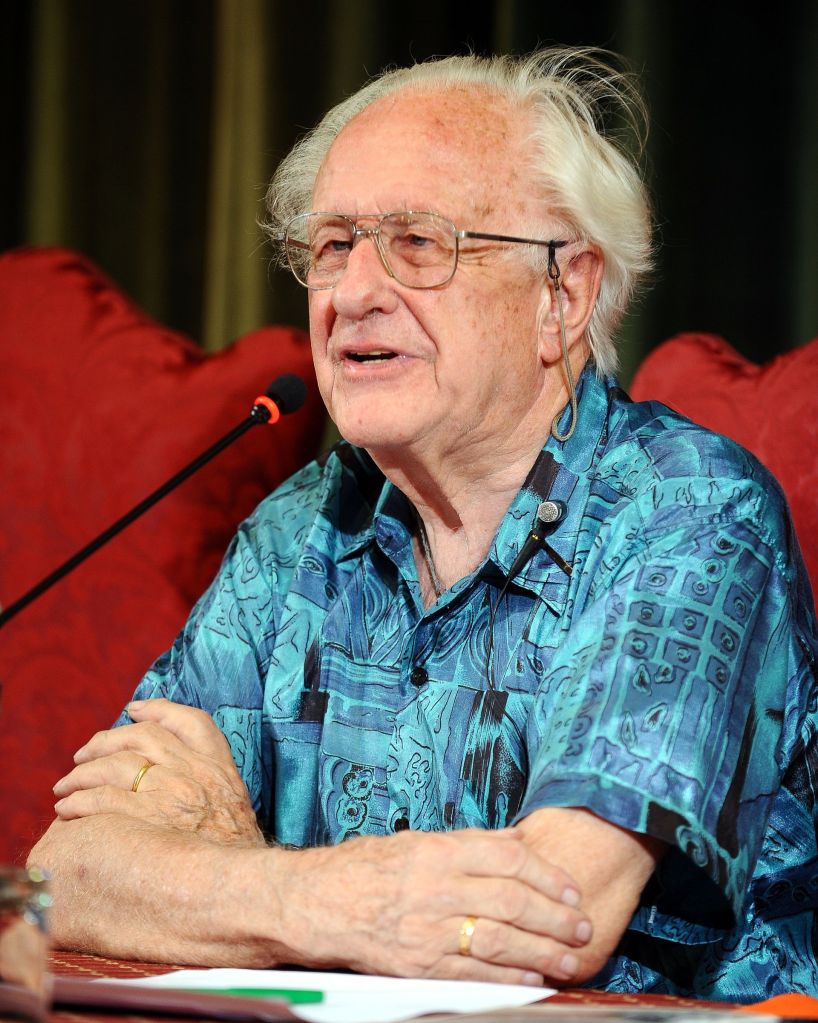

“The second project of the West, secularism, started undermining transcendent religion, leaving human beings deprived of Father-Sky, with no Mother-Earth as alternative, and only small groups (Quakers, Buddhists) still insisting on the sacred nature of life, particularly human life. And this is exactly Formation IV [post-modernism]; for secularism, in the shape of humanist ethics, has not been capable of producing binding norms for human behavior. Why shall you not commit adultery, kill, steal, and lie when other humans are mere objects and there is no accountability to higher forces as there is no transcendent God anyhow? The final result is the total anomie of Formation IV, with human beings left with the only normative guidance that always survives: egocentric cost-benefit analysis. The point is not normlessness, the point is that they are not binding; that is the meaning of culturelessness. The process has gone quite far.” – Johan Galtung (1930-2024), the Norwegian sociologist who first coined the term “structural violence”. Volume II, p. 12.

End-of-Life Care

“People connected to community related centers and community medical professionals have been very welcoming to me as a Buddhist chaplain. Compared to the high barriers of working in hospitals as a Buddhist chaplain, it has certainly been easier to be accepted by community medical personnel. National policy has recently started to emphasize the localization of medicine, which includes the development of community related centers. However, there is still quite a bit of confusion about what this really means and how to carry such policy out. I think this is why temples with a history of being grounded in the community have been welcomed as a way to carry out this policy.” – Rev. Ito Ryushin 伊藤竜信 (1973) Jodo Pure Land priest & certified Buddhist Chaplain (臨床仏教師 Rinsho Bukkyo-shi). Volume II, p. 84-85.

“When we think about our history with temple members, we have known them since they were children, and we have probably known their parents and grandparents as well. Through this long connection, we can work together with caregivers if the person is suffering from dementia, has a chronic disease, or is facing imminent death. Since we have an idea about their sense of value, we can advocate for the patient or support them especially in their final days. This is one of the important roles that we as priests can play.” – Rev. Okochi Daihaku 大河内大博 (1979) Jodo Pure Land priest, co-founder of Satto Sangha Home-Visit Nursing Station (2020) & former Vihara priest at Nagaoka Nishi Hospital. Volume II, p. 84-85.

“The function of temples as a window of consultation can be superior to other types of social work facilities. Through the close relationships between priest and parishioner that Funeral Buddhism has promoted for hundreds of years, a priest can access a believer more easily. A priest can intervene in various domestic problems that are hard for other social workers to do. In this way, more people will be helped without increasing the burden on a priest if such particular social resources are connected to a network of services.” – Rev. Taniyama Yozo 谷山洋三 (1972), Jodo Shin Otani Pure Land priest & co-founder of the Interfaith Chaplain (臨床宗教師 Rinsho Shukyo-shi) training program at Tohoku University (2012). Volume II, p. 80-81.

“Buddhist monks are those who take the oath to walk on the path to nirvana. As they control both the passion to live and the passion to die, they neither commit suicide nor attach to living unreasonably. That is one point that they have in common with those who decide to die with dignity. In this way, it is proper to give advice and to help patients make their own decisions when we, as Buddhist monks, are called on.” – Rev. Dr. Tanaka Masahiro 田中雅博 (1946–2017) Shingon Vajrayana priest & co-founder of the Fumon-in medical complex 普門院 (1990). Volume II, p. 71-72.

“I think by going back to our Buddhist origins one more time, we can support the salvation of the mind/heart (心 kokoro) of our patients by entering into their daily lives and those of their families. If we, who have come to work in medicine, do not look at it from the patient’s viewpoint, we have undoubtedly entered the issue ‘with our shoes on’ – that is, we’ve been selfish and rude. The common people cannot accept this from us.” Volume II, p. 71-72.

“I have reservations about the terms ‘spiritual pain’ and ‘grief care’, which many people in Japan now talk about. I feel like they do not know what they are talking about, because Japanese Buddhism, with its wakes and funeral ceremonies and so forth, is all about grief care. Every single year, Japanese make a large fire at the summer Obon festival to welcome back for a few days the spirits of dead ancestors and relatives. As long as we treasure these traditions, then specialized grief care programs should not be needed.” Volume II, p. 70.

“The problem for most Japanese, however, is that they cannot understand why the term ‘spiritual’ should be added to the definition of health. The problem with bringing up religious or spiritual topics is that if people do not accept these topics when they are healthy, then when they become sick, there won’t be any room to accept them. By that time, they are just struggling to live. After becoming hospitalized is not the time to begin religious dialogue.” – Dr. Hayashi Moichiro 林茂一郎, founding director of the Department of Palliative Care and Vihara Ward at the Kosei Hospital run by the major new Buddhist group Rissho Kosei-kai. Volume II, p. 55.

“I feel it less important for priests to develop new doctrinal and ritualistic applications for dying than it is to become deeply involved with the very experience of death by engaging directly with people before they die. This is the real way to recover Buddhism’s role in Japanese society at large. As the dying issue is part of a much larger holistic social problem, by engaging in it actively and directly, we can touch the many other social issues that need our attention today and come to a much broader holistic solution to them.” – Rev. Tomatsu Yoshiharu 戸松義晴, Jodo Pure Land priest & former Chairman of the Japan Buddhist Federation (JBF). Volume II, p. 38.

“As recently as sixty years ago, shortly after World War II, international surveys ranked the Japanese among the least death-fearing people in the world. Within the forty years between 1960 and 2000, among the dozens of countries surveyed, Japan became the most death-fearing country in the world.” – Dr. Carl Becker, professor at the Kyoto University Kokoro (Heart-Mind) Research Center 京都大学こころの未来研究センター and renowned thanatologist. Volume II, pp. 48-49.

Suicide Prevention

“For Japanese, we believe in an incredible vast expanse of life (命 inochi) that interconnects (縁 en) with those who have lived before. We carry the life forward and relay it, even with animals and plants, etc. In this way, we try to make our service [for the bereaved of suicides] non-denominational as the participants come from a variety of religious and non-religious backgrounds.” – Rev. Fujio Soin 藤尾聡允 (1957) Rinzai Zen priest & co-founder of the Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Self-death and Suicide. Volume II, p. 131.

“Suicide is one of the various ways of death, like disease, accidents, murder, and so forth. Heaven and hell, however, is a different matter and is not directly related to suicide. To try to answer the question of who goes to heaven and who goes to hell, one needs to start talking about what are the bad deeds that lead to hell. This is a matter of one’s own religion or denomination. ‘Who goes to hell?’ is a profound question. In our association’s understanding of Buddhism, the spirits of the suicidal are in heaven or the Pure Land through the welcome of the Buddha no matter how they died. – Rev. Fujio Soin 藤尾聡允 (1957) Rinzai Zen priest & co-founder of the Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Self-death and Suicide. Volume II, p. 119.

“When I talk with people who are contemplating suicide, I can see their point and sympathize with them. I’ve learned through experience that I can’t save anyone. I try to create an atmosphere that makes it possible for them to share their problems. It might take time and I might have to try different things. There is no manual or one right way.” – Rev. Nemoto Jotetsu 根本紹徹 (1972) Rinzai Zen priest & director of the Association of Religious Professionals Confronting Life (Nagoya) (2009).

“Since I myself have not attained enlightenment, I cannot liberate anyone by my own will. However, I can communicate warmth to someone who is suffering before me. In modern Western thought, human life consists of body and mind, but in Buddhist thought, life is defined by breath and heat or warmth. For those people who need support, an interpersonal encounter can help lighten their feeling of isolation by transmitting warmth to them.” – Rev. Takemoto Ryogo 竹本了悟 (1977) Jodo Shin Hongan-ji Pure Land priest & co-founder of Sotto the Kyoto Self-Death & Suicide Counseling Center (2010). Volume II, p. 109.

“People who are filled with anxiety, when walking past a temple, might suddenly feel like going in and confiding in the priest. But from the gate to the entrance seems far. In order to restore the temple as a community center there needs to be preparation. At this stage, telephone consulting is something we [priests] can do outside of the temple.” – Rev. Fujisawa Katsumi 藤澤克己 (1961) Jodo Shin Hongan-ji Pure Land priest & co-founder of the Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Self-death and Suicide. Volume II, p. 103.

“If a salary man faces a problem and cannot do his work well, he then develops a kind of inferiority complex. At this time, he never thinks about what kind of teaching Buddhism could provide; which was true even for me when I faced this situation [as a computer engineer]. When my personal evaluation was low and inferiors humiliated me, I got depressed and asked myself, “Why can’t we develop human relationships well?” I had a feeling that Buddhist teachings had no direct connection to my situation. However, if there could appear at these times a priest who has concern and radiates a feeling of personal intimacy, I think Buddhism could become part of this world and not be aloof.” – Rev. Fujisawa Katsumi 藤澤克己 (1961) Jodo Shin Hongan-ji Pure Land priest & co-founder of the Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Self-death and Suicide. Volume II, p. 102-03.

Disaster Trauma & Chaplaincy

“I feel that there is not much that separates the trained from the untrained, that aspiration is really the key. If you truly care, you can do the work. If this is not your work to do, then you won’t do the work. You won’t do the service. You won’t be engaged in compassionate care. It is not everybody’s job. I think it is fine that people want to create systems and standards, but I think it can prevent more good from happening and does not stop so much of the bad. For example, I know many people who are certified at the highest level as religious personages, professional psychologists, and psychiatrists but who are unsympathetic and unable to do this work. They have spent so much time getting certification that their own hearts have not awakened. You can try to train people in presence, but this is not how it works. Meditation is helpful in this regard. There are all kinds of games and techniques, but it is in a way a natural gift. Moreover, one’s aspiration really matters in this kind of vocation.” – Rev. Joan Jiko Halifax (1942) founder of the Being with Dying: Professional Training Program in Contemplative End-of-Life Care (BWD) at Upaya Zen Center, New Mexico. Volume II, pp. 186-87.

“Offering contemplative care means to be really grounded in our bodies. This allows for sensitivity. It also helps to open up a field of feeling to know what is happening in myself and to become very attuned to the person I am with. I think this is what really allows for spontaneity, to be able to move here or there, for whatever seems to be needed.” – American Zen Buddhist chaplain from the New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care. Volume II, p. 172.

“In traditional Zen, tea is taken in a simple and direct manner in order to objectively re-examine one’s own practice and one’s own daily existence through conversation with one’s Zen master and co-practitioners. This is a very important time for the practitioner to develop mindfulness and to return to one’s own essence. Gyocha as an activity in deep listening to victims during a disaster is about holding and embracing the physical and psychological stress of the victims and offering them a chance for respite while being caught in unavoidably constrained circumstances with no immediate prospects for their future. In this way, we have sought to develop mutual communication as companions experiencing this same life. In terms of the daily drinking of tea in the disaster areas, our activities have aimed to help the victims slowly recover their own beings and way of daily life through sharing tea and dealing with the difficult reality together.” – Rev. Kyuma Taiko 久間泰弘 (1970) Soto Zen priest & President (2009–11) of Soto-shu Youth Association (1975) & gyocha 行茶 cafés (2007). Volume II, p. 158.

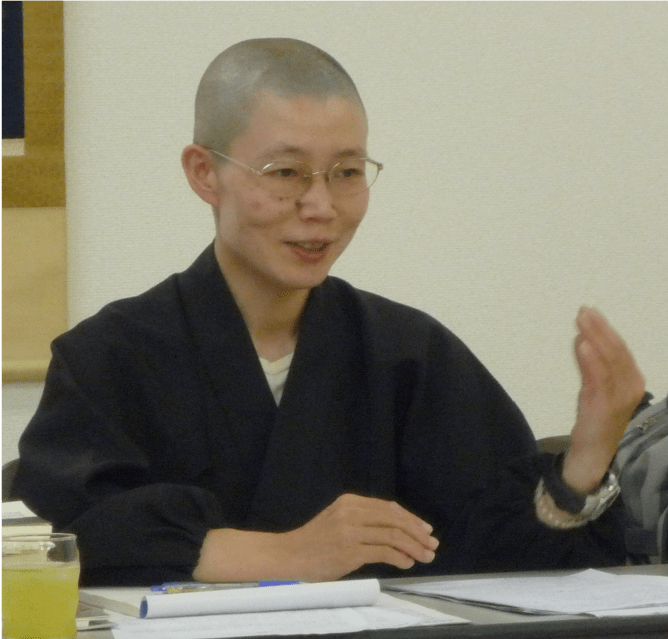

“A more concrete step that religious professionals, specifically Buddhist priests, can participate in is the work of grief care as preventive medical care. A group of temple members can be described as a group of the bereaved. Therefore, there are sympathetic feelings to be shared among temple members. Temples are also needed as a place to gather, and grief care is provided when they go to their affiliated temples to participate in a memorial service. What I mean by grief care here is not what a priest provides, but rather it is a kind of peer counseling where people who share grief get together and talk. In this way, translating grief care into religious activities can be considered an unfinished issue.” – Rev. Iijma Keido 飯島惠道 (1963) (Soto Zen nun and palliative care nurse) Yakuozan Tosho-ji temple 薬王山東昌寺. Volume II, p. 153.

“For Buddhist priests in Japan, the first opportunity to connect with people, especially those traumatized by loss and death, is at funerals and memorial services. It has been heartening to learn directly from many of the victims in the disaster areas of their positive feelings towards Buddhist priests and their activities at this time through comments like, ‘Just listening to the voice of the Buddhist priests chanting saved me.’ Buddhist priests, however, need to take this opportunity to go deeper into an intimate interaction rooted in active listening. In terms of Buddhist practice, this is related to the Four Practices of the Bodhisattva (四摂法 shi-shoho) in relating to people. The fourth such practice (samanarthata, 同時 do-ji) is especially important as it refers to working together by putting oneself on the same level as others and participating alongside them in activities. This can be further explained as putting oneself in the place of others and listening deeply without getting caught in one’s own view. The idea is to listen as Kannon Bodhisattva would. However, it is not usual for religious professionals to have received training in such deep listening, and especially for Buddhist priests, this can be a high hurdle to get over.” – Rev. Jin Hitoshi (1961) 神仁 founder of the Rinbutsuken Institute for Engaged Buddhism (2008) & Buddhist Chaplaincy (臨床仏教師 Rinsho Bukkyo-shi) training program (2013). Vol. II, p. 175.

Voices from the Tsunami

“Our attitude was ‘to smile’. In order not to succumb to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), we thought about how to have fun when at all possible. On the first day, we decided on a family council. When a victim wanted to talk, we tried as much to make them smile and to make a joke about things. Every morning, we held a chanting service, and I gave a simple dharma talk and tried to make it enjoyable. At first, people would only smile a little bit, but gradually they would burst out laughing. As a result, we could do our work in a lively and spirited way. It has indeed been a very difficult experience, and there have been many people whose mental balance has collapsed. In this kind of situation, the important thing is that people must speak up at all costs. We have been continuing to remind them, ‘If there is anything, come talk to us.’ Because of stress, it is easy for arguments to break out, so before trouble arises, I try to get in between people and mediate by listening completely to both sides.” – Rev. Shibasaki Eno 芝﨑惠應 Nichiren priest & abbot of Senju-in Temple 仙寿院, Kamaishi City, Iwate. Vol. II, p. 144.

“I didn’t dare approach these people like a religious leader. With each individual victim, I wanted to connect like a family member… we have little idea where to start and towards what direction we should head. However, until the final person is relocated into their temporary housing, I know that we want to provide for them.” – Rev. Koyama Keiko 古山敬光 Rinzai Zen priest & abbot of Jion-ji Temple 慈恩寺, Rikuzentakada City, Iwate. Volume II, p. 131.

Rural Decline, Migrant Laborers, Poverty, and Homelessness

“We have four main values for our activities: 1) taking responsibility for one’s own actions and consumption habits by clarifying the greed inside oneself. This does not mean denying it but properly confronting it and managing the way one consumes and lives; 2) not ignoring the laws of nature as humans living in systems that we have created. Buddhism teaches the karmic causality of how proceeding in a certain direction, especially in an unskillful way, will reap specific results; 3) respecting harmony (和 wa), which means tolerance towards diversity by not excluding anyone although one’s personality and values differs from others. This respect is realized through the Buddhist practice of loving kindness and compassion; and 4) accepting that life is not confined to the realms of the rational, scientific, and utilitarian. In the end, we evaluate the work not based on its profitability but it’s goodness or wholesomeness.” – Rev. Yamashita Chisa 山下千朝 (1986) Jodo Pure Land priest & founder of the Amrita Co., Ltd., a social enterprise for rural development

“I think the details of the suffering of these people are not widely known in general society, so this is an important role for us priests in making these voices heard. We would like to make these single parents and their children feel that there are many people watching out for them with a caring eye and ready to offer support. Our activity is to see and listen to this suffering from these families and to recreate a sense of connection with the community and society at large. In this way, we recently we made a new slogan ‘Glad I could count on you’ (頼って嬉しい toyotte ureshii).’ It’s very important to go and meet such people in suffering, to engage in deep conversation with them, and to see their actual life and way of thinking … Our main activity is to cultivate people’s minds to help others and rebuild compassionate Japanese culture all over the country.” – Rev. Noda Shinmyo 野田晋明 (1990) Rinzai Zen priest, certified Buddhist Chaplain (臨床仏教師 Rinsho Bukkyo-shi) & regional head of the Temple Snack Club (2013)

“There are good people and also bad people anywhere you live and work. It has nothing to do with living in the street as homeless. Nor is it connected with being a company worker or a student, where we also find good and bad people. It’s not good to pity them, but it’s also not good to prejudice them as if they have done something wrong. I would like it that they are not painted with one color. Among such good people, I remember one old man who said as I handed him a rice ball, ‘I am so thankful for you coming out in this cold weather. It must be hard for you as your hands have gotten so cold.’ Yet he must have been even colder than us. In this way, we could share a mutual feeling through which prejudice and discrimination is removed. This goes beyond the intellectual understanding that one should never engage in prejudice or discrimination. This is quite intense; if one can come in contact and direct connection with such an experience, I think it will be possible to destroy the problem of discrimination.” – Rev. Yoshimizu Gakugen 吉水岳彦 (1978) Jodo Pure Land priest & co-founder of the Hitosaji “One Spoonful” Association (2009)

“Although there are people who are important to us who are not blood relations, we divide and establish our burial plots according to blood relation. The Sanyu Association has brought together those who basically have no close relations and provides a place for building relations from which one can speak from the heart. It is important to build connections even beyond our blood relations.” – Rev. Yoshimizu Gakugen 吉水岳彦 (1978) Jodo Pure Land priest & co-founder of the Hitosaji “One Spoonful” Association (2009)

“Our view is that something special done by someone special can become nothing special done by everyone. In other words, people should do what everyone can do. This is more important than great works done by only people who have special skills and abilities.” – Rev. Takase Akinori 高瀬顕功 (1982) Jodo Pure Land priest & co-founder of the Hitosaji “One Spoonful” Association (2009). p. 225-26.

“Over forty years, there have been a total of 450,000 people forced to work amidst nuclear contamination. Regulations on the over exposure to radiation have been routinely dismissed. Labor has been used and discarded in a structure of wretched subcontracting … These many sacrifices have foremost been to secure our present way of living. This is just like the suicide kamikaze pilots at the end of World War II … At all times, there has been the demand for quantification, speed, and pleasure, and economism. This kind of awareness supports ‘The Myth of Need’ [for nuclear energy] at its roots.” – Rev. Nakajima Tetsuen 中嶌哲演 (1942) Shingon Vajrayana priest & co-founder of the Interfaith Forum for the Review of National Nuclear Policy. p. 200.

“Meeting with radioactive poisoned workers and listening to their experience changed my life. I first met them when I was a university student at Tokyo University of the Arts. Before meeting them, I was not interested at all in doing social work. However, I was moved by listening to how they have suffered. They suffer from various health problems. In addition, they are mentally damaged by prejudice and misunderstanding.” – Rev. Nakajima Tetsuen 中嶌哲演 (1942) Shingon Vajrayana priest & co-founder of the Interfaith Forum for the Review of National Nuclear Policy. Volume II, pp. 196-97.

“The year 1965 is unmistakably the point at which the village community begins to collapse. Originally, village community was based on cooperative labor. The periods of planting and harvest bound or fastened the community. In mutual association, everyone brought together their energy for work. The bonds of the village were its rules or conventions, and if they were violated, there were penalties, such as being ostracized. In this way, the village community sustained itself. One main rule was that everyone participated in communal labor. Such communal labor could muster great energy to preserve agricultural traditions and methods. However, as communal labor began to decline, the village became increasingly dispersed, and so we have arrived at this present situation.” – Rev. Hakamata Shunei 袴田俊英 (1958) Soto Zen priest & co-founder of the Thinking about Life and Mind Association (2000) and the Yotte-tamo-re Café (2003). Volume II, p. 193.

Nuclear Energy & the Potential for “Buddhist Development” (開発・かいほつ kai-hotsu)

Voices from Fukushima

“Truth be told, when I arrive in Fukushima, driving in my car, I notice how beautiful it is. There is still just incredibly beautiful nature that is unimaginable in urban areas. It is nature that you can no longer find in Western Japan. It still exists in Fukushima, the gateway to Northern Japan. It is a great nature that you cannot escape. There is no place to journey without vegetation. Passing through such great nature in my car, I am overcome with an apologetic feeling, ‘I’m sorry.’ I think this is not the occasion to wear a mask. My heart cries out, while my mind says it’s better to wear a mask.” – Rev. Tanaka Toku-un 田中徳雲(1974) Soto Zen priest & abbot of Dokei-ji 同慶寺 Minami Soma, Fukushima

“In order to decontaminate the premises of the temple, I had to cut down a 100 year old cherry tree located on the kindergarten’s playground. I am continuing to hold meetings in Nihonmatsu for making a temporary storage site for materials that have been contaminated by nuclear radiation, yet still no place has been found. People want to dispose of dangerous materials in far away places, and this kind of thinking is what created the problem of nuclear power. There is no place in the world you can find that is good for such pollution. I have had to bury contaminated materials in one place within the temple grounds and the kindergarten’s playground. Those who have evacuated and those who have remained are both suffering and living their lives while enduring this crime. I cannot forgive the government and TEPCO. I used to be angry inside, but the children saved me from my anger. Seeing these children who can’t freely play outside made me feel as if they were saying, ‘You did this to us.’ I used to think nuclear power had become the norm and was safe. I was indifferent to the Chernobyl and Tokaimura nuclear accidents. Having no feeling for the preciousness of life, I was living as a priest only when convenient for me. I lived like this for 39 years, and in the end it brought suffering to the children. Once I realized that, my mind got clear. I felt relieved and was able to get back on my feet.” – Rev. Sasaki Michinori 佐々木道範 (1972) Jodo Shin Otani Pure Land priest & abbot of Shingyo-ji 真行寺, Nihonmatsu city, Fukushima

“There used to be a tree enshrined as a memorial stupa for dead animals at a forked junction nearby the temple during the 1950s and 60s. There were Buddhist writings on each branch expressing that there is ‘enlightened mind’ (bodhicitta 菩提心 bodaishin) in all living things. That was how much the locals felt close to other creatures.” – Rev. Hoshimi Zen-e 星見全英 Soto Zen priest & abbot of Ganoku-ji, Minami Soma, Fukushima. “Pigs are eating the corpses of cows who have died of starvation. This is the present situation in Iita-te village.” Mr. Hasegawa Kenichi 長谷川健一 a 58-year-old dairy farmer from the infamous town of Iita-te. “May the Cattle of Oba and the Myriad Spirits Attain the Unsurpassed Wisdom of Enlightenment.” a wooden Buddhist mortuary tablet (塔婆 toba), commonly made for humans upon their deaths, nailed to one of the pillars in the cattle barn of Ms. Oba Shoko, age seventy, whose cattle died of starvation tethered to their posts on a property only 10 kms from the reactors in the town of Namie.

“The attacks on Pearl Harbor on December 8, 1941 certainly invited the expansion of a war of aggression as well as the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the great catastrophe of the defeat of our nation that followed. During this time, flowery rhetoric was made of ‘self-sacrifice for one’s country’ (滅私奉公 messhi-hoko) to cloud over the people’s spirit. Buddhists also twisted the true meaning of the Buddha’s concept of not-self in order to send followers off to the battlefield. I ask, how much longer will we continue to accept the same kind of flowery rhetoric used in the beautiful name of Manjusri and other such figures for a national policy that depends on nothing but the increase of spent nuclear fuel and plutonium?” – Rev. Nakajima Tetsuen 中嶌哲演 (1942) Shingon Vajrayana priest & co-founder of the Interfaith Forum for the Review of National Nuclear Policy

“We continued on this path [after the war] with the new tacit slogans “Quit Asia, Enter America” (脱亜入米 datsu-a nyu-bei), “Faith in Scientific Technique” (科学技術信仰 kagaku gijutsu shinko), and “Great Economic Nation” (経済大国化 keizai taikoku-ka). Large-scale production, large-scale consumption, and large-scale disposal, as personified in the giant nuclear power crowd, became an extension of the modernization process since the coming of the Black Ships. At all times, there has been the demand for quantification, speed, and pleasure, and economism. This kind of awareness supported ‘the myth of need’ at its roots. Now, we have to undergo a deep process of self-reflection. – Rev. Nakajima Tetsuen 中嶌哲演

“There was talk about why something wasn’t said more quickly [about the Fukushima disaster]. However, the issue is not about waiting for someone to say something, but rather that anyone who has such awareness should have the courage to just go ahead and say something. I think there are common points with the previous situation of the silence of the Japanese Buddhist world in development of the Pacific War, such as thinking about what is right as well as looking into what is around us … I feel that the war issue and the nuclear issue are the same. They both involved national policy, but not everyone agreed with such policy. There were only a handful of them in both cases, but there were people who opposed and courageously made warnings. However, this never became a large voice, and so we met with disaster made by this massive mainstream. On this point, nuclear power and the war followed the same trend.” – Ven. Kono Taitsu 河野太通 (1930) Rinzai Zen monk & Rinzai Myoshin-ji sect chief priest 2010–14 & Japan Buddhist Federation Chairman 2010–2012

“Even if the (denomination’s) parliament decides to view the Fukushima problem without linking it to the war-time issue, it may still be difficult to build a consensus. What may typically happen is paralysis by analysis. One MP may insist that, ‘The government is saying that the problem is under control, and this kind of accident will never happen in the future. Why should we make a critical statement, if that is so?’ Another MP may point out that, ‘We know that some of our parishioners work within and on the edges of the nuclear power industry. If we make a critical statement, we will end up harming them.’ These kinds of discussions were actually repeated in and out of the parliament sessions of some denominations. Discussions like these only breed confusion, not decision. If this is the state of the highest decision-making body, one can easily imagine that it will tend to keep the status quo rather than take on new challenges.” – Rev. Okano Masazumi 岡野正純3rd Presidentof the Kodo Kyodan Buddhist Fellowship 孝道教団 & co-founder of the Japan Network of Engaged Buddhists (JNEB)

“Religious professionals should all overcome their differences and overcome their different ways of thinking to unite to protect the lives of children. We need to all get together to discuss how we can love our home region and how we can restore it. In order to do this, religious professionals should really take some leadership. There is a feeling in these areas amongst the locals of really expecting something from us. In this way, my mission from now on is to dedicate myself this work and to live in Fukushima.” – Rev. Tanaka Toku-un 田中徳雲 (1974) Soto Zen priest & abbot of Dokei-ji 同慶寺 Minami Soma, Fukushima

“Young people entering the way of the Buddha must hold fast to and install in their gut the fundamental idea in Buddhism of the value of sentient life and respect for human rights. I want them to speak and act with courage in anything they do. Not just in the time of the war, but even today, there are many people who do not speak the truth because of the prevailing stance in society. Buddhists don’t really need to care about prevailing social trends, so they should speak out clearly. I would like them to think that their role as abbots is to say what is right and to protect sentient life and human rights.” – Ven. Kono Taitsu 河野太通 (1930) Rinzai Zen monk & Rinzai Myoshin-ji sect chief priest 2010–14 & Japan Buddhist Federation Chairman 2010–2012

“When we Buddhists get involved in social movements, I believe the foundation of our engagement is the Four Noble Truths. The starting point is clear awareness of the real situation and empathy with those who are suffering; the second step is to look for the causes and mechanisms of this suffering in a logical and objective manner; thirdly, we look at the ways that we can bring about an end to this suffering and what sort of ideal society we want to achieve as a result; and finally, we take concrete effective action to achieve our vision. For myself, this journey into the suffering of others leads to a really deep self-examination and examination of my own country. From this examination and a reflection on my own Buddhist values, the choice of a human centered society rather than an industrial centered society became clear to me. Indeed, the Buddha’s teaching of the Four Noble Truths is an organic process which if practiced properly leads from the experience of suffering to critical reflection and then naturally to an embrace of the value of human relationship and sentient life.” – Rev. Okochi Hidehito 大河内秀人 (1957) Jodo Pure Land priest & co-director of the Interfaith Forum for the Review of National Nuclear Policy

“The first step is conscientization to social issues and the rights of the people. It is important for social activists, which includes Buddhist priests, to conscientize the people that it is their duty to actually pressure the government and fight rather than to just be in despair and to complain. While Buddhist priests should not mobilize people through anger, they should encourage the people to rise up.” – Ven. Paisan Visalo, a renowned Socially Engaged Buddhist monk in Thailand, after visiting the Fukushima region in November 2012

“I therefore urge a rapid transition to an energy policy that is not reliant on nuclear power. Japan should collaborate with other countries that are at the forefront of efforts to introduce renewable energy sources and undertake joint development projects to achieve substantial cost reductions in these technologies. Japan should also take on, as its mission, efforts to promote the kind of technological innovation that will facilitate the introduction of new energy sources in developing countries that currently struggle with this issue. In effecting this transition, it is necessary that adequate measures be taken to foster alternative industrial bases in communities that have been economically dependent on nuclear power generating facilities and have contributed to the national power supply … In point of fact, the damage to both human health and the natural environment from exposure to radioactivity is exactly the same for an equivalent dose whatever the source – the actual use of nuclear weapons, the release of radioactivity accompanying the development, production and testing of these weapons, or an accident at a nuclear power plant.” – Ikeda Daisaku 池田大作 (1928-2023) the third-generation leader of the Nichiren lay denomination Soka Gakka

Civilization

Civilization“Each generation shall endeavor to preserve the foundations of life and well-being for those who come after. To produce and abandon substances that damage following generations is morally unacceptable. Given the extreme toxicity and longevity of radioactive materials, their production must cease. The development of safe, renewable energy sources and non-violent means of conflict resolution is essential to the health and survival of life on Earth. Radioactive materials are not to be regarded as an economic or military resource.” – Joanna Macy (1929) American Buddhist environmentalist from her Nuclear Guardianship Ethic

“We have to honor and own this pain for the world, recognizing it as a natural response to an unprecedented moment in history. We are part of a huge civilization, intricate in its technology and powerful in its institutions, that is destroying the very basis of life … People fear that if they let despair in, they’ll be paralyzed because they are just one person. Paradoxically, by allowing ourselves to feel our pain for the world, we open ourselves up to the web of life, and we realize that we’re not alone … The response that is appropriate and that this work elicits is to grow a sense of solidarity with others and to elaborate a whole new sense of what our resources are and what our power is.” – Joanna Macy (1929) American Buddhist environmentalist

“The Buddhist philosophy of autonomy and self-sufficiency might give light to our choice. It indicates the end of an individualistic value system that has forged the ideological basis for a modern world system characterized by the constant increase of production, the pursuit of a profit-oriented mind as well as consumption (greed), increasing waste and the accelerating deterioration of the human environment, and ultimately the increase in conflicts and war….the Buddhist philosophy of development would support a direction towards a new page of the post-economic growth history of humanity. This is also an opportunity for the revival of Buddhism in Japan.” – Prof. Nishikawa Jun 西川潤 (1936–2018) development economist, Waseda University

“These days, we want to enable people to feel a warm connection with others and to create a world in which no one has to feel alienated or alone. Our ultimate goal is to develop community around the Buddhist temples that are found everywhere in Japan so that no one has to feel left out and everyone can feel connected. The temple was the center of such local community for many centuries in Japan in the past. We want to emphasize creating connections in a society in which desire is not the determining factor. Such a society is a place where we can be connected beyond differences in race and religion and where we can also have an economic system that is based on sustainability rather than desire. We are trying to make a mechanism based on Buddhist ethics that is not based on desire, taking what is not given, or conflict over resources but is rather based on a sense of mutual trust and sharing.” – Rev. Takemoto Ryogo 竹本了悟 (1977) Jodo Shin Hongan-ji Pure Land priest, co-founder of Sotto the Kyoto Self-Death & Suicide Counseling Center & co-founder of Tera Energy (2018)

Afterword

“As a Marxist, I value the classics. The classics have been read for hundreds of years. In them there is a kind of universality and guiding principle that is different from the values and techniques of capitalism, and that is why I read Marx. In the same way, religion has a timeless universality and sustainability that is not dependent on growth. That is what I hope to see in it … Buddhism and religion were originally based on a totally different philosophy than the one of constant growth. They have remained for hundreds or even thousands of years in the form of tradition, so in this respect, they are sustainable. In other words, they have been sustainable without depending on growth.” – Prof. Saito Kohei 斎藤幸平, author of Marx’s Capital in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism.

“These are all manoeuvres to turn religious faith into a private matter and thus remove it from topics that are susceptible to debate in the public sphere. To these conservatives, even if a problem of the kind identified by the women’s movement did exist, it could be reduced to a merely personal and individual issue that has nothing to do with social justice. Therefore, religious faith can be used as a rationale for suppressing attempts to denounce discriminatory practices.” – Prof. Kawahashi Noriko 川橋範子 (1960) co-founder of the Tokai-Kanto Network of Women and Buddhism (1994)

“I have seen many male priests who are enthusiastic about environmental issues and social contribution suddenly become unaccepting when it comes to gender issues … Most of the priests who are active in ‘social contribution activities’ (社会貢献活動 shakai ko-ken katsudo) and attract media attention are men”. Prof. Kawahashi Noriko 川橋範子 (1960) co-founder of the Tokai-Kanto Network of Women and Buddhism (1994)

“The Buddha said, ‘May all beings be happy.’ It clearly says so in the sutras. The Buddha spoke out against what we call today as ‘discrimination’. The LGBTQ+ community is a minority but society caters to the majority, making life difficult for minorities. Buddhism does not accept that. It is our role to be allies, to embrace them and their needs. We are working to create an inclusive society. Rev. Nishimura Kodo is active as an artist. He puts on makeup and wears gorgeous clothes. He’s also active as a priest. Both are true. I hope to see him do more great things. We support him.” – Rev. Tomatsu Yoshiharu, Jodo Pure Land priest & former Chairman of the Japan Buddhist Federation (JBF)