Articles & Activities

Gender Equality & Justice

Can Buddhism “Make Your Life Beautiful”? Gender in Japanese Buddhism – Ms. Misa Seno (2025)

A Sangha for Peace & Inclusivity: Intersectionality in Gender Work in Japan (2024)

Gender, LGBTQ, and Discrimination—The Wish for the Well-being of All People – Ms. Kaori Matsuzaki (2020)

End-of-Life Care

End-of-Life Care & Buddhist Naikan Therapy – Rev. Mari Sengoku (2022)

One Dies as One Lives: The Importance of Developing Pastoral Care Services and Religious Education – Rev. Mari Sengoku (2012)

Amans: A Buddhist Nun’s Efforts to Unite the Medical and Religious Worlds in Death – Rev. Keido Iijima (2012)

Suicide Prevention

A Priestess’ Role in Civil Society – Rev. Eka Shimada (2014)

Disaster Trauma & Relief

Maintaining the Dignity of People in Such a Severe Situation – Ms. Yuko Suda (2011)

Smiles on the Faces of the Children of Fukushima – Rev. Eka Shimada (2011)

Buddhist Holistic Development

Depopulation and Regional Development: Reviving local communities through alternative lifestyles based in Buddhism – Rev. Chisa Yamashita (2020)

Edogawa Citizen’s Network for Thinking about Global Warming (ECNG)—Soku-on Net (scroll to the bottom) – Ms. Yuki Nara (2025)

International Cooperation & Advocacy – Ms. Mika Edaki (2020)

Disarmament & Peace

Working for National and Global Peace – Ven. Yuki Yako

Introduction to Gender Issues in Japanese Buddhism

The Problematic Issue of the “Temple Family and Wife” (ji-zoku)

Over the last decade, we have seen broad endorsement in Japan of the United Nations 17 Social Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by its member states in late 2015. Gender equality occupies point number five among the seventeen overall goals. Yet after many advertising campaigns and events to promote the SDGs in Japan, the Asahi Shimbun reported in June 2022 that Japan’s SDG ranking has steadily gotten worse from the position of 15th in 2018-19 to 17th in 2020, 18th in 2021, and 19th in 2022. One of the key areas dragging their rating down has been gender equality. “The dismal performance in gender equality is attributable to the disproportionately low ratio of female lawmakers and a wide pay gap between men and women.”[1] Indeed, no matter which index one examines – such as the 2023 World Economic Forum Global Gender Gap report that rates Japan 125th out of 156 countries or the 2023 World Bank report[2] that listed Japan 121st out of 153 countries – gender equality is a persistently difficult issue in Japan.

In terms of the Buddhist world in Japan, a great shift occured in the opening to modernization in the Meiji period (1868-1912). Buddhist monks were gradually laicized in the 1870s first with the “meat eating and marriage” (肉食妻帯 nikujiki saitai) policy that deregulated state control over, and enforcement of, the Buddhist monastic vinaya and then with policies that classified priests as “common citizens” (国民 kokumin), who had to register as belonging to a household, even as a “temple family” (寺族 ji-zoku). While many high-ranking monks, such as the Jodo patriarch Fukuda Gyokai 福田行誡 (1809–1888), opposed these policies, many others advocated for clerical marriage. Well-known reformists from the Buddhist Enlightenment Movement (仏教啓蒙活動 Bukkyo Keimo-katsudo), Inoue Enryo 井上円了(1858–1919) and Shimaji Mokurai 島地黙雷 (1838–1911), fused Western trends in eugenics and evolutionism with old feudal notions of untouchability and caste to argue that monastic celibacy was anti-modern, anti-scientific, and unpatriotic. They heralded the genetic superiority of their own Jodo Shin denomination for its tradition of marrying priests to the best women of the community, rather than the marginal types of women who had illicit affairs with the celibate monks of other orders.[3] Under this new tide, it was estimated that by the middle of the Meiji era some forty to fifty percent of all Buddhist priests were married, indicating this was already a common practice that was not done openly due to general disapproval from parishioners. In a survey from 1936 by the Soto sect – which doctrinally has strong, traditional regulations on celibacy – families lived in more than eighty-one percent of temples.[4]

The influence of this era on the normative role of the Japanese Buddhist male priest in the modern era is obviously fundamental, yet this era also marks the emergence of the particular issue of gender in modern Japanese Buddhism with the nebulous status of the “temple family” (寺族 ji-zoku), a term that now often refers simply to the wife of the abbot. As the modern Buddhist temple came to replicate, and even willfully live up to, the social standards established by the Meiji government and succeeding administrations, ji-zoku came to take on the same roles as common housewives in their patriotic role to raise sons for the new society. In this case, the sons inherit the temple through a blood lineage as had been happening in the Jodo Shin order for centuries. Ironically, what was considered a dangerous and deeply heterodox movement in the Kamakura era in the general Pure Land, but particularly Jodo Shin, movement became the common standard for all traditional Buddhist sects in modern Japan. The result, as Kawahashi Noriko 川橋範子, one of the leading scholars and activists on gender issues in Japanese Buddhism today, notes is “the core problem” of “the fictitious principle of the priestly renunciation of secular life, which is a major factor obstructing equality for both sexes in Japanese Buddhism today.… The problem arises because the Buddhist orders have made no serious move to face this fact openly, but instead continue even today to maintain a stance of ostensible priestly renunciation of secular life.”[5]

Beyond forcing such ji-zoku into such hetero-normative social roles, the results of this attitude are numerous and include: 1) with the lack of acknowledged status, a lack of opportunity to cultivate themselves as practitioners much less as leaders in the sangha; 2) a lack of decision making power, especially in the governance of the wider denomination as seen in the almost total lack of women in denominational parliaments;[6] 3) the threat that if they are unsuccessful in raising a male heir, they can be pushed out of the temple when their husband dies with no claims to the home they have built; 4) at the time of death, they may be buried separately in small graves while their husbands are buried in much larger ones with previous abbots;[7] 5) being confined to the duties of raising children and of the temple world prevents ji-zoku becoming active in wider social activities, for example Socially Engaged Buddhist ones, that their husbands more freely access. While this would seem to be a more serious issue in the orders whose doctrines promote rigorous monasticism, such as the Soto and Rinzai Zen orders as well as the Tendai, Kawahashi notes that, “Uncritical acceptance of the status of bomori [in the Jodo Shin order] as a recognized wife also constitutes wilful disregard of the various elements of discrimination encoded in that status.”[8]

Another critical point of Kawahashi’s indicates how traditional Buddhist denominations have further internalized the ethic of the separation of religion and state promoted in the modern era. This problem occurs not only through their reluctance to take stances on social issues but also in the reluctance to face gender discrimination within their orders in light of trends towards women’s empowerment in wider society. She comments, “These are all manoeuvres to turn religious faith into a private matter and thus remove it from topics that are susceptible to debate in the public sphere. To these conservatives, even if a problem of the kind identified by the women’s movement did exist, it could be reduced to a merely personal and individual issue that has nothing to do with social justice. Therefore, religious faith can be used as a rationale for suppressing attempts to denounce discriminatory practices.”[9] From the perspective of the Socially Engaged Buddhist system of the Four Noble Truths, this is a classic example of obscuring structural and cultural violence through appeals to the failed agency of individuals. It is also a problem of the persistent power of modern Japanese institutions to turn general, patterned issues of social injustice into case-by-case incidents that do not require paradigm shift.

When such thinking is clarified in the Second Noble Truth, a different result occurs in a new awareness of solidarity among those in suffering. Kawahashi notes that, “Dialogue extending beyond schools and sects has brought women to understand that their individual experiences of gender discrimination were culturally and historically structured.”[10] Such dialogue has manifested itself in the establishment of the Tokai-Kanto Network of Women and Buddhism[11] in 1994. While rather small in number, Kawahashi explains the network as “a diverse group of people…including wives of male priests, female priests (nuns), women who are a combination of both, and women who do not belong to any particular Buddhist order… Their project, in brief, is to enlarge women’s voices in the Buddhist community by a variety of means, including autonomously organized workshops, publication of workshop findings, formation of networks across sectarian boundaries for information exchange, and, by means of women’s participation, to transform present-day Buddhism to provide equality for both sexes.”[12] The basic character of a network that goes “beyond the boundaries of the various denominations” fits well into the definition of movements ascribed to the activities of Socially Engaged Buddhists in other fields such as suicide prevention and anti-nuclear activism.

Created in the early 1990s, the network was more an outgrowth of the feminist movements in Japan of the 1970s than a direct response to the Disconnected Society of the 2000s as with most of the more recently created Engaged Buddhist networks in Japan. While the postwar era saw the rise of women in numerous social movements, such as the peace campaigns against nuclear war of the 1950s and the environmental movement of the 1970s, women often acted more within the modern hetero-normative container of “wife and mother” fighting for the future of their children than from a wider field of social justice and social transformation. Such activism gave way to trends in the 1990s referred to as “state feminism” (国家フェミニズム kokka feminizumu), which “predicts that a state institute could rectify gender discrimination and then could improve gender relations in the society.”[13] Again, Buddhist denominations have replicated these wider social patterns rather than challenge them; for example the role of women’s associations (婦人会 fujin-kai), with the Soto denomination’s environmental campaigns of the 1990s, and with the efforts of rank-and-file Soka Gakkai members to pressure the Komei-to party to stand by its commitments to preserving Japan’s peace constitution. Although small and marginal, the Tokai-Kanto Network of Women and Buddhism represents something different. It not only “envisions a new Buddhism that empowers present-day lay women [through] reinterpretation of conventional, male-centered Buddhist history and doctrine in light of women’s own experiences.” It also has “the goal of extend[ing] well beyond mere criticism of Buddhism.” In this way, the Tokai-Kanto Network appears aligned with other feminist and gender movements in the wider Socially Engaged Buddhist world, such as the International Women’s Partnership for Peace and Justice[14] based in Thailand, which see the potential of Buddhist teachings and practices to shift modern social stances on gender. However, linkages between the Tokai-Kanto Network and such groups are not well developed.

Socially Engaged Buddhism and Gender: Bhikkhuni vs. Ji-zoku

Gender as both a problem within Buddhism and a problem in wider society would, therefore, seem to be a particularly opportune issue for Socially Engaged Buddhists (SEB) to engage in, yet Buddhism’s long historical struggle with patriarchy has kept it from being a more prominent part of the SEB movement. Kawahashi Noriko has noted that in terms of Japanese Socially Engaged Buddhism, “I have seen many male priests who are enthusiastic about environmental issues and social contribution suddenly become unaccepting when it comes to gender issues.” She also comments that, “Most of the priests who are active in ‘social contribution activities’ (社会貢献活動 shakai ko-ken katsudo) and attract media attention are men”.[15]

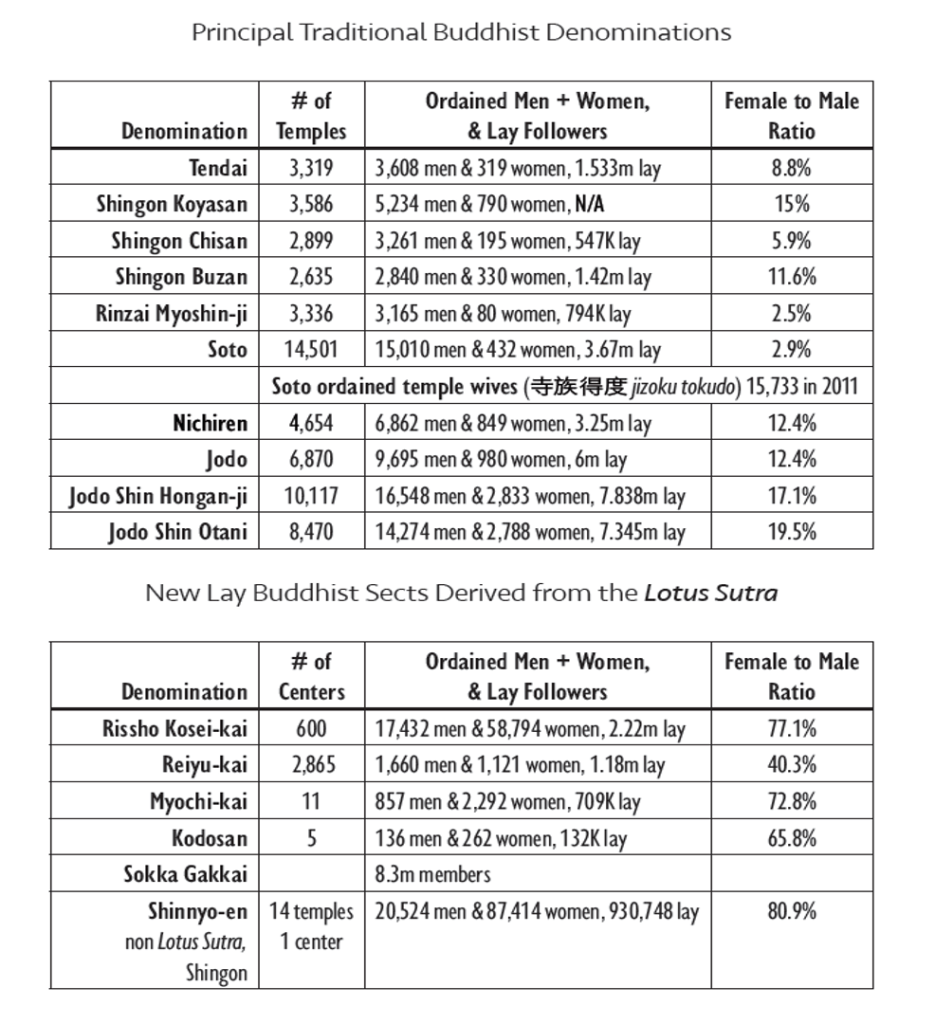

Despite JNEB’s attempts to highlight the work of a number of Socially Engaged Buddhist women active in social issues, Kawahashi’s above statements still largely ring true. In examining JNEB’s national network map, 17 Socially Engaged Buddhist women are listed amongst a total of 89 activists, that is, 19% of the entire network. While this compares favorably to the ratio of 3-8% of ordained female teachers in the more monastic orders of Japanese Buddhism, it is about the same for the Jodo Shin orders and significantly below the new lay Buddhists orders, where women leaders often outnumber male ones, especially at local levels. Thus, Socially Engaged Buddhists also seem to have been unable to awaken to the importance of the gender issue.

The SDGs as a Skillful Means for Gender and LGBTQ+ Empowerment?

While cooperative activities with Buddhist women outside of Japan are not well developed, the SDGs may provide a “skillful means” (upaya 方便 hoben) to make the gender issue a more urgent priority in the Japanese Buddhist world and help connect Buddhists to wider trends in the secular world. In this vein, the Buddhist NGO AYUS–whose director Edaki Mika and board member Ms. Seno Misa 瀬野美佐 a Soto sect administrator, are active members in the Tokai-Kanto Network–have recently created on-line seminars on the SDGs and gender in Japanese Buddhism. Ryukoku University, under the Jodo Shin Hongan-ji order, has also held similar such symposiums as AYUS and has established the first “gender-based religious research institute” in Japan called the Gender and Religion Research Center (GRRC).[17] Going beyond the confines of the hetero-normative categories of men and women, the SDGs movement in Japan has also brought the LGBTQ+ issue to greater prominence. On November 5, 2020, the Japan Buddhist Federation held an on-line public symposium entitled “Buddhism and the SDGs: What is Equality in Buddhism in Today’s Society from an LGBTQ+ Perspective?”.[18] Chaired by JBF’s then director and a well-known Socially Engaged Buddhist, Rev. Tomatsu Yoshiharu (Jodo), it featured another Jodo denomination priest Nishimura Kodo 西村宏堂, who a few years ago became public about their sexuality and gender. Nishimura has become a media sensation as an international makeup artist who, when not wearing Buddhist robes for official ceremonies, may be seen in a variety outfits, even ones that make them look like Kannon Bodhisattva come to life.

A critical issue is how such LGBTQ+ persons in Japan may often be ostracized from their family grave plots and end up becoming “disconnected spirits” as mu-en hotoke 無縁仏. Japan is also well behind other parts of the world with similar economic and political systems in terms of allowing for marriages between same-sex and transgender people. According to the Dentsu Diversity Lab, the percentage of LGBTQ+ people in Japan is 8.9%, and certainly this includes the Buddhist ordained Sangha, which actually has a long history of homosexual culture. However, the promotion by the state of hetero-normative nuclear families from the Meiji era through the postwar era has pushed Buddhist priests away from the more vague gender identity of celibate monastic and into the more clearly defined one as father and salary-man for the “temple family”. Recently, a few Socially Engaged Buddhists priests have indicated an ambivalence towards marriage and procreation while developing a different kind of post-modern “temple family” and community. Indeed, it will be interesting to see how Rev. Nishimura ages and builds their temple community as chief priest. There are also now priests who are openly conducting marriages for LGBTQ+ persons. Another speaker at this symposium, Kawakami Zenryu 川上全龍, a priest of the Rinzai Myoshin-ji denomination, has begun actively accepting LGBTQ+ wedding ceremonies at his Shunko-in Temple 春光院 in Kyoto. The temple has partnered with Hotel Granvia Kyoto to offer package tours for Buddhist weddings for LGBTQ+ couples. Rev. Kawakami notes, “The temple’s attitude of ‘welcoming coming out’ is really important. We should visualize that temples are safe zones for LGBTQ+ people.” In this way, the JBF has helped sponsor the design of rainbow-colored stickers with the Buddhist greeting of palms together that temples can display as a sign that LGBTQ+ persons are welcome and safe at this temple.

Two years before that seminar in 2018, the JBF under Rev. Tomatsu’s leadership formally announced its support for the LGBTQ+ community. Rev. Tomatsu explains, “The Buddha said, ‘May all beings be happy’. It clearly says so in the sutras. The Buddha spoke out against what we call today as ‘discrimination’. The LGBTQ+ community is a minority but society caters to the majority, making life difficult for minorities. Buddhism does not accept that. It is our role to be allies, to embrace them and their needs. We are working to create an inclusive society. Rev. Nishimura is active as an artist. He puts on makeup and wears gorgeous clothes. He’s also active as a priest. Both are true. I hope to see him do more great things. We support him.”[19] In some ways, it seems that the Japanese Buddhist world is much more quickly embracing the LGBTQ+ issue than the women’s issue, once again exposing the deeply ingrained patriarchy of Japanese society. Whether the SDGs can form a real platform to take on these various issues that the Japanese Buddhist world has turned a blind eye to or whether it will just provide another social trend for Buddhist to ride in their attempt to appear contemporary and relevant is yet to be seen. This struggle, indeed, has been the saga of Buddhism in Japan since the advent of modernity in the Meiji era.

This article is excerpted from the Afterword in: Watts, Jonathan S. An Engaged Buddhist History of Japan Vol. II: A New Socially Engaged Buddhism in 21st Century Japan: From Intimate Care to Social Ethics (Ottawa: Sumeru Books, 2023) pp. 305-329.

[1] Hokugo, Miyuki 北郷美由紀. “Japan’s world ranking in meeting SDG goals falls to 19th”. Asahi Shimbun. June 2, 2022.

[2] Sakakibara, Ken 榊原謙. “Japan ranks last among developed states regarding gender equality”. Asahi Shimbun. March 3, 2023.

[3] Jaffe, Richard. “Meiji Religious Policy, Soto Zen, and the Clerical Marriage Problem”. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 1998. Vol. 25, No. 1-2. pp. 70-71.

[4] Ibid., pp. 31-32.

[5] Kawahashi, Noriko. “Re-Imagining Buddhist Women in Contemporary Japan”. In Handbook for Contemporary Japanese Religions. Eds. Inken Prohl & John K. Nelson. (Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill, 2012), pp. 200-01.

[6] Only 2% of the members of denominational parliaments (宗議会 shugi-kai) of the ten major traditional Buddhist sects are women. In the Jodo Shin Hongan-ji sect, for example, there are no female members. “Japan’s first Gender-based Center for the Study of Religion” (日本初 “ジェンダーを基軸とした宗教研究拠点”とは Nihon-hatsu jenda-wo kijiku-toshita shukyo kenkyu kyoten-to-ha). ReTACTION: Web Magazine for Everyone’s Buddhism and SDGs. September 1, 2021. https://retaction-ryukoku.com/508

[7] Kawahashi Noriko. “Jizoku (Priests’ Wives) in Soto Zen Buddhism: An Ambiguous Category”. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 1995. Vol. 22, No. 1-2. pp. 174-75.

[8] Kawahashi. “Re-Imagining Buddhist Women in Contemporary Japan”. p. 201.

[9] Ibid., p. 204.

[10] Ibid., p. 205.

[11] Tokai-Kanto Network of Women and Buddhism (女性と仏教東海・関東ネットワーク Josei-to Bukkyo Tokai Kanto Nettowaku).

[12] Kawahashi. “Re-Imagining Buddhist Women in Contemporary Japan”. pp. 204-05.

[13] Kobayashi, Yoshie. A Path Toward Gender Equality: State Feminism in Japan. (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2004), p. 2.

[14] For more on the work of IWP, see Khuankaew, Ouyporn. “Buddhism and Domestic Violence: Using the Four Noble Truths to Deconstruct and Liberate Women’s Karma”. In Rethinking Karma: The Dharma of Social Justice. Ed. Jonathan S. Watts. (Bangkok: International Network of Engaged Buddhists, 2014), pp. 199-224.

[15] Kawahashi, Noriko 川橋範子. “What should a sustainable religious community look like?” (持続可能な宗教界はどうあるべきか Jizoku kano-na shukyo-kai-ha do-aru-beki-ka?). In The Earth and Its People Seen from the Eyes of Fieldworkers (フィールドから地球を学ぶ Fuirudo-kara chikyu-wo manabu). Eds. Satoshi Yokoyama 横山智編 et. al. (Tokyo: Kokon Shoin Publishers Ltd. 古今書院, 2023), p. 38. https://www.kokon.co.jp/book/b621043.html

[16] Of the cohort of 21 candidates who in December 2022 stood for examination to move on to the final stage of internship in clinical settings 10 were women and 11 were men. Of the 10 fully certified Buddhist chaplains to graduate from this program since its beginning in 2013, 4 are women and 6 are men.

[17] The Gender and Religion Research Center (GRRC) 龍谷大学ジェンダーと宗教研究センター Ryukoku Daigaku Genda-to Shukyo Kenkyu-senta).

[18] All quotes and references are from Ukai, Hidenori 鵜飼秀徳. “Discrimination against LGBTQ Continues even after Death: The Critical Problem of the Taboos on Graves and Posthumous Names:” (LGBTQへの差別は死後も続くタブー:視されてきたお墓と戒名の大問題 LGBTQ-he-no sabetsu-ha shi-go-mo tsuzuku tabu: Shisaretekita ohaka-to kaimyo-no dai-mondai). President Online. November 13, 2020. https://president.jp/articles/-/40405?page=1

[19] “A Monk Who Wears Heels”. NHK World documentary. March 5, 2022. 15:00-15:45.