Learning from the Theory and Practice of Buddhist Development (kaihotsu)

日本語の報告

Harsha Navaratne

Chairperson, International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB)

“We build the road – the road builds us.”

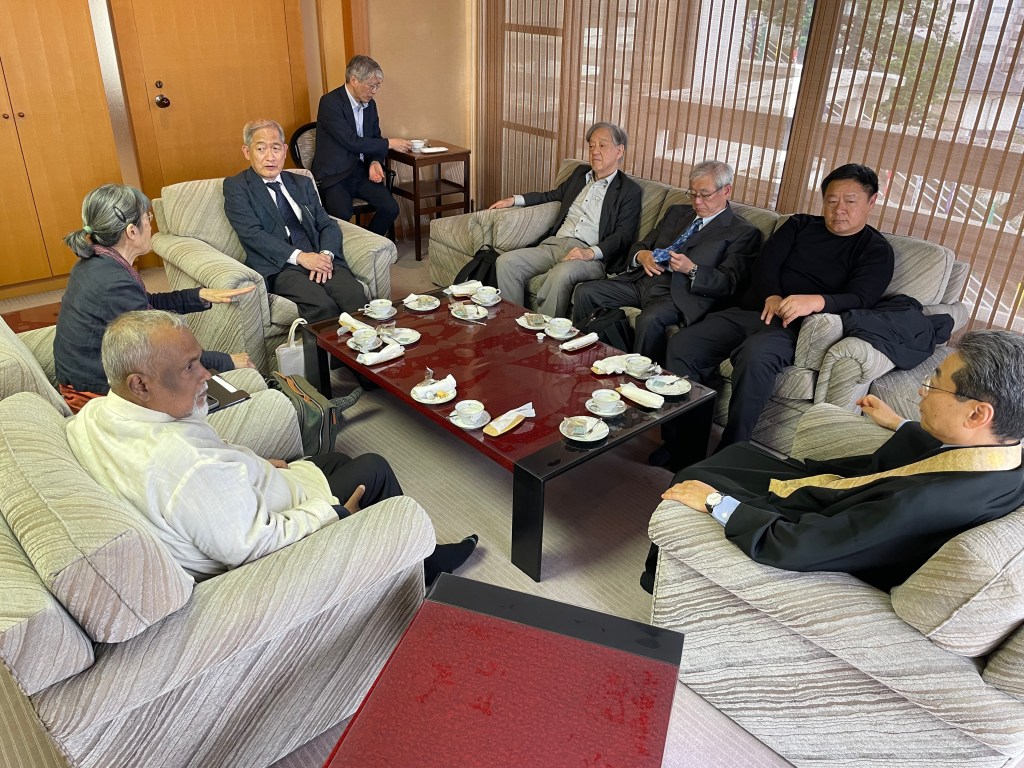

The 3rd annual public symposium of the the Buddhist Social Ethics in Contemporary Japan Study Group was held on May 9, 2025 at the main temple of the Kodo Kyodan Buddhist Fellowship in Yokohama with cooperation from its International Buddhist Exchange Center (IBEC). This year’s symposium further explored North-South cooperation and solidarity among Buddhists and civil society, with the concrete activity plans evolving out of these symposiums.

Buddhism as a Social Movement for Community Development

Let me begin with my journey as a volunteer in a social movement.

After completing my high school education, I was looking for an apprenticeship to become a mechanical engineer at a tractor company. My grandmother took me to meet my uncle, who was then a teacher at one of Colombo’s leading schools. Coincidentally, he invited me to join a village development program, where he was leading a group of students participating in a work camp to build a road.

We were there for a week, and after we returned, he asked me, “Would you like to go and stay in a rural village, continue this kind of work, and learn more?” I was excited and happy to accept the offer before I decided to start my mechanical engineering apprenticeship.

Interestingly, that short visit became the beginning of a lifelong journey as a full-time development worker. I have walked from one corner of the island to the other, lived in many villages, and travelled to nearly one-third of Sri Lanka’s 14,000 villages. For two decades, I worked alongside my uncle, who became my guru, and together we served communities until I eventually moved on, away from him and the organization.

My guru, teacher, was none other than the late Dr. A.T. Ariyaratne, the founder of the Sarvodaya movement.

As volunteers in a social movement, we went into villages and became part of the community. The villagers welcomed us as members of their own families. Everyone referred to each other as “father”, “mother”, “sister”, or “brother”—never by name. Over time, we became deeply familiar with each other.

Traditionally, the temple was always the focal point of the village in Sri Lanka, both culturally and socially. The head monk provided moral leadership, and on the full moon days, the temple bells rang, and the entire village gathered at the temple. This is where the community discussed any ongoing issues, solutions, and collective actions to address problems. The Sarvodaya movement based its activities on this traditional model.

If it were a community infrastructure project—a road, a water resource, a school, or a sanitation system—people would agree on a set date. On that date, the entire village came together. It felt like a festival: mothers and sisters prepared meals for everyone; the young and the old shared the physical work; and any technical support came from nearby towns. By the end of the same day, the project was completed.

This is why we said, “We build the road – the road builds us.” Physical infrastructure was built through collective effort and labour, but most importantly, the moral, ethical, and social values that lead to personal transformation and inner awakening were practiced and integrated. The village built its road, but the community gained something deeper—a mentally, ethically, emotionally, and culturally mobilized individual who became an integral part of the village life.

Through these community engagements and activities, dedicated village leaders rose up, and they spread the message of community engagement from one village to the other–within a few years, these community projects expanded into 7,000 villages around the country. Importantly, the citizens understood the difference between political parties and social movements committed to social development.

This is how rural Sri Lankan communities with the support of Sarvodaya built one of the world’s most remarkable social movements within a few decades.

Many foreigners and outsiders who visited to observe these community engagements realized that it was the legacy of Buddhist practice and cultural heritage that gave our nation the strength and self-reliance to pursue its path for social development.

The Problem of Development from the Outside and the West

I would now like to consider development projects from the First World and how they have affected countries like ours in terms of benefits and challenges.

Since the 1960s, the Western model for community development emerged to address poverty by considering the needs of local communities. It was about delivering resources and services from first-world countries to third-world countries. Many bilateral and multilateral organizations call this process “development cooperation”. Conceptually, they promoted a “people-first” approach to development, aiming to create sustainable projects that alleviated poverty and drove economic growth.

However, these approaches to development by Western countries often lacked a true understanding of local cultures and customs. Many such interventions faced criticism and ultimately failed.

For those of us who support participatory democracy and grassroots development, we realized that such assistance created dependency on resources in communities. Unfortunately, these donor-driven programs turned local initiatives, social movements, and community engagements into top-heavy institutions that weakened the grassroots impacts. These initiatives have damaged community structures by turning rural and regional leaders into paid workers.

In this way, there are two types of development cooperation: The first type is bilateral and multilateral cooperation. The second type is non-governmental assistance through civil society partnerships. Over the past fifty years, we have seen Western countries frequently shift their priorities and tag-lines to suit their own interests, often without consistent alignment with local needs.

Many times, under the name of “sustainable development”, Western planners are designing and strategizing local development in their own countries in the West. But at the end of the day, no matter how much you strategize or plan, the implementation has to be done by the recipient. To be fair, there have been a few international NGOs that have focused on development by partnering, participating, and cooperating with local communities.

Let me take a moment to quote a comment by an independent researcher:

Over the last fifty years, Western world development priorities have shifted from primarily focusing on economic growth and modernization to encompassing a broader range of goals, including social development, environmental sustainability, and global health. Early efforts emphasized industrialization and material development, while later decades saw an increased focus on poverty reduction, human rights, and environmental protection.

If these latter objectives are not fulfilled, can a development project be truly considered as successful? If these projects and programs don’t improve the everyday life of local people, how is it possible to have long-term sustainable development?

From our experience, most of the donor-funded projects focus more on design and planning than on tangible, realistic outcomes. These initiatives promote neoliberal values and globalization, which are more aligned with expanding foreign markets and business interests than empowering local communities.

When globalization was first proposed, it was presented as an opportunity for economic growth, access to international markets, increased information flow, cultural exchange, and the promotion of diversity. But today, in Asia, in our part of the world, globalization has led to a cultural crisis—a loss of traditional values, exploitation of local resources, and increased competition for goods and markets.

As academics have pointed out:

Globalization can both positively and negatively affect locally driven development. It can create new economic opportunities and provide access to global knowledge and technology. However, it can also lead to job losses, the commercialization of culture, and the depletion of local resources due to market pressures.

The Future and Potential for Partnership with Japan and the Southern Regions of Asia

Fortunately, North and South civil activism and development partnership has been much more participatory and inclusive.

Our experience with Japanese development assistance has been more diverse and sustainable than Western development approaches. Many countries, like Sri Lanka, received technical training and knowledge to support sectors such as infrastructure development, education, public health, and more.

However, other than development-oriented foundations, assistance from Japanese civil society is sadly lacking in due process and constructive outcome. Japanese civil society groups have supported and provided donations and have been involved through personal relationships. However, their local partners in Sri Lanka have done nothing for local communities or the country. The individuals involved gained personal wealth from such donations, including Buddhist monks who have built up their assets. Sharing this information has become one of our main concerns during our visits to East Asia in the past few years. This situation has to change. It is important to look at the outcome as well as the impact.

As engaged Buddhists and development practitioners, we have a strong and crucial role to play in creating a sustainable future for our communities and our countries. There are examples of practices and experiences of like-minded individuals, organizations, and communities in Japan. So let’s focus on building a space for partnerships with people so that they can share, learn, and expand their knowledge, skills, experiences, and resources.

We—in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Asia—share similar values, culture, and deep historical links. Such connections are very important for peace, stability, and prosperity. Let’s avoid the ongoing geopolitical rivalries driven by the world powers. Who knows if our part of the world will also be involved in a crisis like the Middle East? Let’s avoid such situations. Some of you are doing great work with your communities, and we face daily challenges. So why not unite these efforts? Let’s build a strong, efficient, and impactful network—one that drives meaningful, positive change across regions.

Let me end with a quote from the Secretary-General of the United Nations:

This is a time like no other for all people to raise their voices and engage in our global community. We are living in turbulent times. Our planet is burning, conflicts are raging, and inequalities are deepening. Human rights are under fire. Mistrust and misinformation are polarizing people and communities. But none of this is inevitable. Time and again, humanity has shown that when we unite to tackle our greatest challenges, change is possible.

Commentary: Rev. Arima Jitsujo and Buddhist Development (kaihotsu)

Toshiyuki Osuga

Shanti International Volunteer Association, Special Advisor

Lecturer, Soto Zen Research Center

The Shanti Volunteer Association is a nongovernmental, Buddhist international cooperation organization established in 1981. It is mainly engaged in educational and cultural support projects in Asia, especially in the Indochina region, as well as disaster relief projects in Japan and other parts of Asia. (For more on the Buddhist NGO movement in Japan see A Brief Overview of Buddhist NGOs in Japan, 2004)

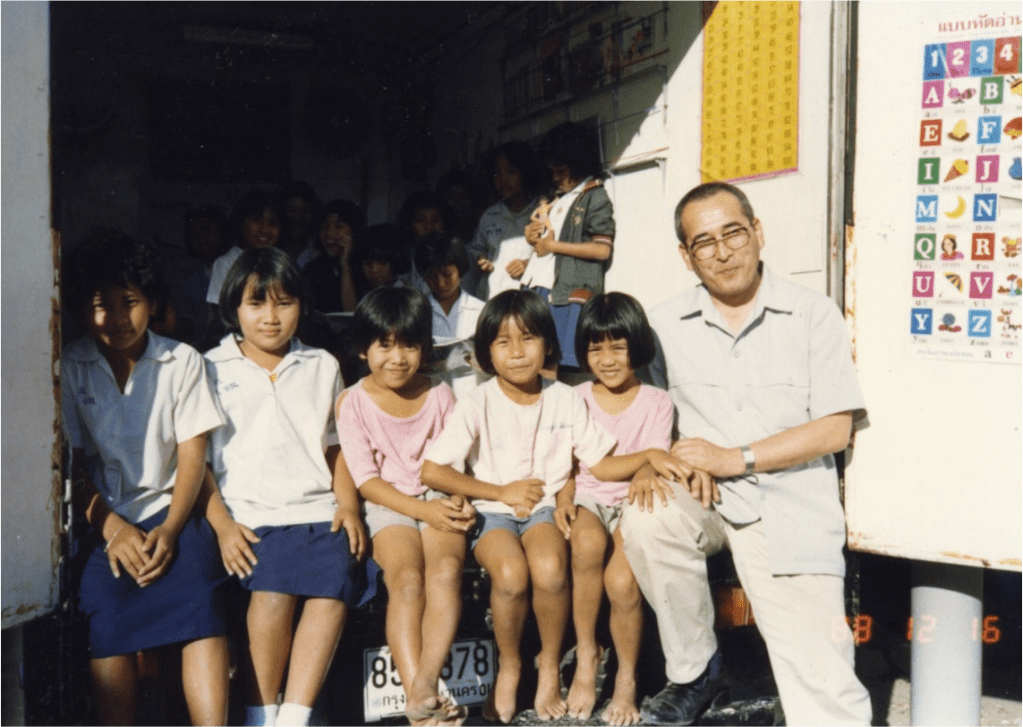

The founder of our association, Rev. Arima Jitsujo, often said that we should learn from the Sarvodaya Shramadana movement (in Sri Lanka) and development monks (in Thailand) and made this one of the guiding principles of our activities. In this sense, I am very grateful to have had the opportunity to listen to Harsha’s talk today. In light of what he said, we would like to explore the Buddhist concept of development (kaihotsu) through what Rev. Arima was thinking.

1. Profile of Rev. Arima Jitsujo (1936-2000)

Rev. Arima was the hereditary abbot of Genko-ji Temple of the Soto Zen sect located in Shunan City, Yamaguchi Prefecture. He was the founder of the Shanti Volunteer Association, the former President of the Japan NGO Center for International Cooperation (JANIC), and the former Vice President of the Tokyo Disaster Relief Volunteer Network, a leader in the NGO world. In February 2025, he was selected as one of the important 100 Buddhists of the Showa era (1926-1989) in a survey conducted by the Bukkyo (Buddhist) Times newspaper.

2. The Spiritual Center of Arima — Eison

Eison (1201-1290) was a monk of the Kamakura period (1185-1333) who was concerned about the decadence of Buddhist monks at the time. With a call to “return to Shakymuni Buddha”, he strove to uphold the monastic precepts and at the same time devoted his energies to social relief activities.[1] Under the slogan of “bestow the Dharma for the benefit of sentient beings” (興法利生 koho risho)”, he restored the Saidai-ji Temple in Nara as a center for the restoration of the precepts, established the subsect of the Shingon sect called the Shingon Ritsu school (ritsu meaning precepts), and taught the precepts to many people. At the same time, he undertook various social relief projects, such as helping people suffering from leprosy, building bridges and harbors, and establishing temples and shrines.

3. Learning Bodhisattva Practice from Eison’s Manjusri Sutra as Buddhist Volunteerism

Rev. Arima learned the following ideas from Eison’s Manjusri Sutra (“Monju Sutra”). Poor and isolated people are not beings to be pitied. They are living manifestations of Manjusri, the bodhisattva of wisdom. The poor and isolated are the ones who are trying to retrieve the treasure of wisdom in Manjusri from their ordeals. Manjusri has the power to bring others to life. When we engage with them with respect, we too can be part of that power.

4. Ocha-mori: “one taste, one mind; one taste, one mind in harmony”

Tea ceremony in Japan originated with Eison. He attempted to create a spiritual and religious community of “one taste and one mind; one taste, one mind in harmony”. This is a community that lives together with the common people by taking advantage of the sociability of tea. Rev. Arima said: “Even if we just preach equality and know the absurdity of discrimination, we must first fight against the “inner mind of discrimination” that lurks within us. In this way, Eison also said that through this tea ceremony, we must be in harmony with one another with the same mind of compassion. In other words, I believe that Eison was conveying the message that we should abandon the division between “those who help” and “those who are helped”, while supporting each other as equals with one heart.

5. Chogen: The Image of the Monk as a Networker and the Origins of the Buddhist NGOs

Chogen (1121-1206) was also a monk of the Shingon sect who practiced at the Daigo-ji Temple in Kyoto. He was considered a Buddhist saint and practiced mountain asceticism. He travelled to Song dynasty China three times and built various halls and Buddhist monuments. He also undertook civil engineering projects, such as the construction of roads, bridges, harbors, and the repair of reservoirs. In the late Heian period (1181), he was appointed as the Daikan-jinshoku to oversee the entire project of rebuilding the Great Buddha at Todai-ji Temple in Nara. Using his extensive personal connections, he organized the wisdom and power of the people and, using his detached hermitage (別所 bessho) as a base, completed the Great Buddha, the Great Buddha Hall, the South Gate, and other surrounding facilities over a period of 22 years.

6. Networking through Development Potential

Chogen’s “honoring one’s true abilities” (本領発揮 honryo-hakki) is manifested in the way he managed his “hermitage”. He nurtured people, drew out their potentials, and carried out business by making the most of his network. A bessho or hermitage is a place where saints and practitioners originally lived as a base of activities. The bessho established by Chogen was a complex facility that was not only a religious institution but also served as a terminal for groups of engineers, an agency for procuring materials, a welfare facility, and a vocational training center. The project to rebuild the Great Buddha at Todai-ji Temple was carried out by a network of seven bessho. The main players in this project were people living at the grassroots, that is, the many people whose names are not known.

7. Gyoki: the Original Founder of Connecting Buddhism and Social Work by being close to the people

Gyoki (668-749) was a monk who became ordained at the age of 15. He is known to have studied the teachings of mind-only of the Yogacara school and practiced in the mountains and forests until the age of 37. After that, he worked to help people suffering from poverty, famine, and epidemics. He worked on civil engineering projects, such as irrigation canals and boat landing sites in rural areas. Although he was criticized for violating the rule on monks and nuns not doing missionary work in the city, he was enthusiastically supported by the people. In 743, at the order of Emperor Shomu, he played a central role in the construction of the Great Buddha at Todai-ji Temple.

8. Buddhists who Connected “the Development of the Mind” and “the Development of Society”: Gyoki–Chogen–Eison—Arima

Buddhist “development” (kaihotsu) is to manifest the latent abilities of everyone, to awaken to the true nature of the world’s various problems, to develop true humanity, and to strive for the perfection of character. The development of society includes the development of the mind rather than the pursuit of material wealth driven by greed. In other words, we aim for balanced overall development.

9. Experiences in the Cambodian Refugee Camps

In 1980, when Rev. Arima set foot in a Cambodian refugee camp, a refugee donated to him what little milk he had, saying, “I am glad that you came all the way here for us.” Arima was so moved that he recalled Eison’s words, recalling, “Isn’t this what Eison meant by seeing Manjusri through the eyes of the impoverished and isolated?” The giver also becomes the receiver. The receiver also becomes the giver. This is the discovery of the three-wheeled emptiness (purity) of generosity (dana). The giver, the receiver, and the gift support each other on an equal footing.

10. Human Beings Need Nourishment for the Mind (the power of culture)

Rev. Arima began to create small libraries in the Cambodian refugee camps, but he was criticized as to the necessity of them. He said the children said to him, “Sweets are gone after you eat them, but picture books are better than sweets because you can enjoy them over and over again”. It was at this point that time he became convinced of how important the power of culture is for human beings, saying, “We consider the culture of the common people for the common people to be important. Culture is the wisdom and skills that enable people to draw out the power and the joy to live and to live with vitality, no matter what the conditions are. Thus, schools exist.”

11. Meeting with Development Monks

A “development monk/nun” (開発僧 kaihotsu-so) is a monk or nun who works to solve social problems and develop society by developing the mind based on the Buddha Dharma. Maha Ghosananda, the great Cambodian peace monk, said, “A true friend is a friend in need”, a figure who stands by people in their suffering. Luang Pau Naan was a Thai development monk who worked with villagers to develop the community. Rev. Arima once said, “I saw Eison in Luang Pau Naan. They are true mahayana Buddhists.” The Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement is a people-oriented development movement for material and spiritual development. Rev. Arima said, “We should learn a great deal from Asian people and Buddhists who see the reality of suffering through the Four Noble Truths and strive to find a way to overcome it together with local people.”

12. Buddhist Development (kaihotsu) in Japan and Asia

Through my talk, we have seen three different lineages of Buddhist development (kaihotsu)

- Ancient Japan: Gyoki, Chogen, Eison

- Modern Japan: Arima & the the Buddhist NGOs

- Southern Asia: Sarvodaya, Thai Development Monks, Engaged Buddhism

13. Contemporary Significance

Global divisions and conflict, natural disasters, social isolation, the light and darkness of AI, and so forth are driven today by greed and the pursuit of economic value and convenience. In this way, we have forgotten the development of the heart, which is a malnutrition of the mind. The need for development of society with spiritual well-being and the development of the mind is is a cue for the role of Buddhist development (kaihotsu). One of the concepts and words missingfrom the SDGs is “culture”. So I ask, is this just a lack of recognition of the power of culture and the development of the mind or is such an attitude simply rare ? The UNESCO Charter highlights a famous correspondence between Einstein and Freud in which the former expressed, “The power of culture deters war and brings peace.” The sentiments have been echoed in Japan by Muneyoshi Yanagi, the founder of the folkcraft movement in the 1920s, and Genyoshi Kadokawa (1917-1975), a well known publisher, as well as in contemporart times by Svetlana Alexievich, a Belarusian writer awarded the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature. These figures show us how we should actively propose the development of both material and spiritual aspects.

14. 80 Years After the War: Living as a Global Citizen

To become a “citizen” is to become a person who recognizes the problems faced by society and community as their own problems and acts independently. Such a person listens humbly to other opinions and values and has the ability to relativize themself. Buddhist monks should also have a sense of citizenship, which translates to social ethics. Living as “global citizens” means the entire world cannot survive without mutual support. We must think of the world as one community, respect each other, and live together in harmony. However, we must not force our own values and worldview on others, as was done in the past with colonial aggression. We must know the pain of the Asian people suffered in the war and rebuild their trust.

[1] Translator’s note: Pure Land Buddhism gained widespread popularity during the Kamakura period and featured the teaching that the monastic precepts and meditative as well as wisdom practices were of no avail in this time of decadence. All that was left was to call on the name of Amida Buddha to gain salvation in the next life. Eison and Nichiren were two well-known monks who opposed this trend and called for a return to the way of Shakyamuni.

Comment by Ms. Yuki Nara

Representative Director

Edogawa Citizen’s Network for Thinking about Global Warming (ECNG)—Soku-on Net

Activity History in Edogawa Ward

- 1985: Moved to Edogawa Ward

- 1986: Gave birth to second child in February

- 26 April: Chernobyl nuclear power plant accident occurred

- 1988: Joined Seikatsu Club Consumer Cooperative

- 1989: Participated in activities to directly request the Tokyo Metropolitan Government to enact a Food Safety Ordinance. Supported a woman who was a board member of the local consumer cooperative in the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly election, Go for it! Election Meeting (Sore Senkai) established.

- 1990: Co-founded the Edogawa Consumers Network with members who had participated in the direct petition campaign.

- 1991: Elected as a member of the Edogawa Ward Assembly.

- 1995: Re-elected for a second term.

- 1999: Stepped down from the ward assembly.

Since then, as the secretary-general of the Edogawa Consumers Network, I supported the newly appointed ward councillor while I also took on a managerial role at the neighbouring shared NPO office Komatsugawa Citizen Farm. With the loss of my council member title, the nature of my participation in activities I had previously been involved in without publicly disclosing my name has changed. I have become the representative director of the environmental NPO Edogawa Citizen’s Network for Thinking about Global Warming (ECNG), known as Soku-on Net. I have also become the chairman of “Mirai-sha”, which handles lending operations for the Mirai Future Bank. I have also been involved in the establishment and operation of various organisations, including the Edogawa Children’s Ombudsman, and continues to do so today.

Before I encountered Seikatsu Club, I had serious concerns about the environment and was frustrated that politics was not addressing those concerns. Despite this, I had no faith in existing political parties and had become a cynical bystander. Through direct petitions for food safety regulations and encounters with people addressing issues like “waste” and “water”, I realised that I had been complaining without taking action.

I began to investigate things that seemed off and activities to create “peace of mind” for ourselves. Sharing uncertainties and concerns with others, rather than passing the responsibility to the government or local authorities, I learned through cooperative activities to seek transparent information and citizen participation to drive change ourselves. Life is determined by politics. We must turn that politics into a tool for our lives.

The Consumer Network activities, born out of the Seikatsu Club Cooperative’s work, are based on the idea of collectively purchasing the power of politicians. We do not view politicians as individuals with special privileges, but as public servants whose authority should be shared by all. Therefore, politicians rotate positions, elections are funded through donations and volunteer work, and anyone can become a politician. By promoting and strictly adhering to these rules, we have overcome the discomfort of being in the unfavourable position of politicians and have been able to move forward without wavering, even when faced with new challenges.

The policies of the Edogawa Consumer Network were immature when it was first established. We actively participated in the movements of other citizen groups engaged in various activities in the region. Among these, a study tour to Sarawak State in Malaysia became a catalyst for broadening our international perspective. We witnessed the reality of Japan importing large quantities of tropical timber for disposable use and the international commercial activities of clearing virgin forests to create massive plantations—activities that exploited indigenous peoples and destroyed sustainable livelihoods.

After I stepped down from the ward assembly, I organised several study tours to Cambodia targeting young people, where we learned together about issues related to Japan’s ODA. As Japanese citizens, we have been thinking and acting together with local people about what we can do to address the current situation where our lives and money are depriving communities in the Global South of their livelihoods and exacerbating poverty and inequality.

Within Japan itself, there are various issues such as public works projects, nuclear power plants, military bases, and waste disposal facilities being imposed on local communities due to political power dynamics. This is nothing other than a government with a weak sense of human rights. As citizens, I have been thinking and taking action alongside local communities to consider what we can do and what we should do.

In terms of the current situation, in the local area of Edogawa Ward, we have experienced how citizens engaged in diverse fields can collaborate to create dynamic and interesting community development. The fact that the Soku-on Network and the Mirai Future Bank have been able to continue their activities from their inception despite a lack of funds was largely due to the existence of the Komatsugawa Citizen Farm, a shared office with a 30-year history. The owner of this office is Juko-in Temple, and its head priest, Rev. Hidehito Okochi, who is also the organiser of this initiative. (see this article for a full profile of all of Nara-san and Okochi-san’s work)

As Rev. Okochi has grown older, the time has come to consider passing the torch to the next generation. With the aim of establishing a sustainable system to maintain this structure, a project was launched over three years ago. Last November, it culminated in the establishment of the Rita Citizen Asset Foundation, a public interest incorporated foundation, which serves as a foundation to utilise the temple’s assets for the benefit of the community. This foundation aims to further expand the region’s initiatives in the future.